In the first half of the 1900s, America’s and Ohio’s need for vocation training grew as the country navigated the rise of manufacturing and consumerism. Companies needed workers, and workers needed quality training. Federal funding for vocational education grew in response.

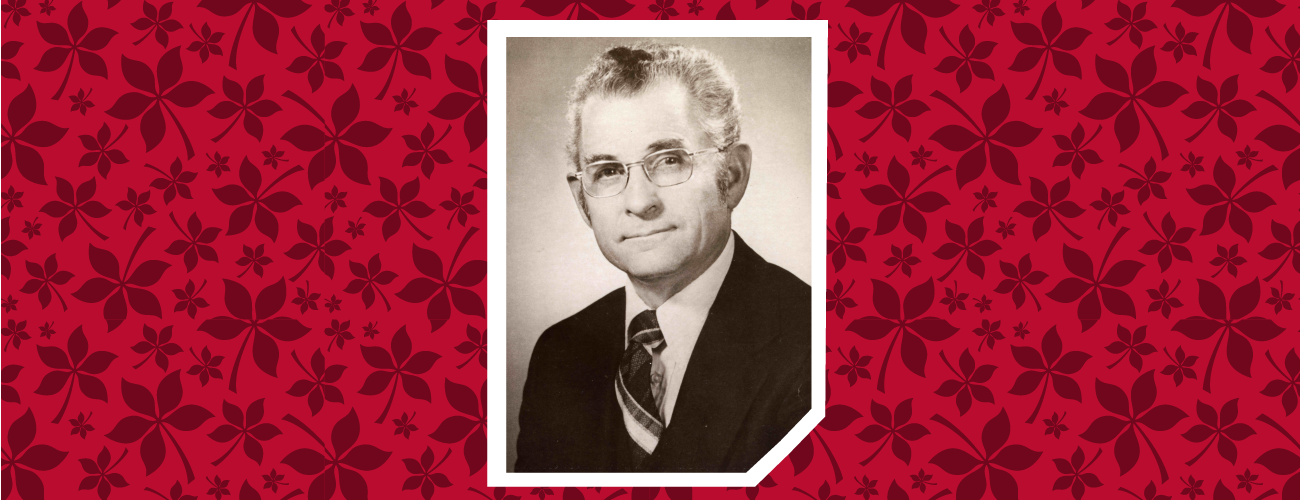

Then, in 1959, Ohio State welcomed a man blessed with the charismatic ability to make meaningful connections that advanced vocational education in Ohio and nationwide.

Robert Taylor arrived to earn a doctorate in the College of Education. Previously from Arizona, he had been state supervisor of agricultural education in the Arizona Department of Education. Within two years, thanks to prior doctoral work in Arizona, he had his PhD and was named an associate professor in the college.

Taylor had been involved for years in Arizona with the national movement to advance 4-H and agricultural and vocational training. So, in 1963, he succeeded in establishing and becoming the director of the Center for Advanced Study and Research in Agricultural Education at Ohio State.

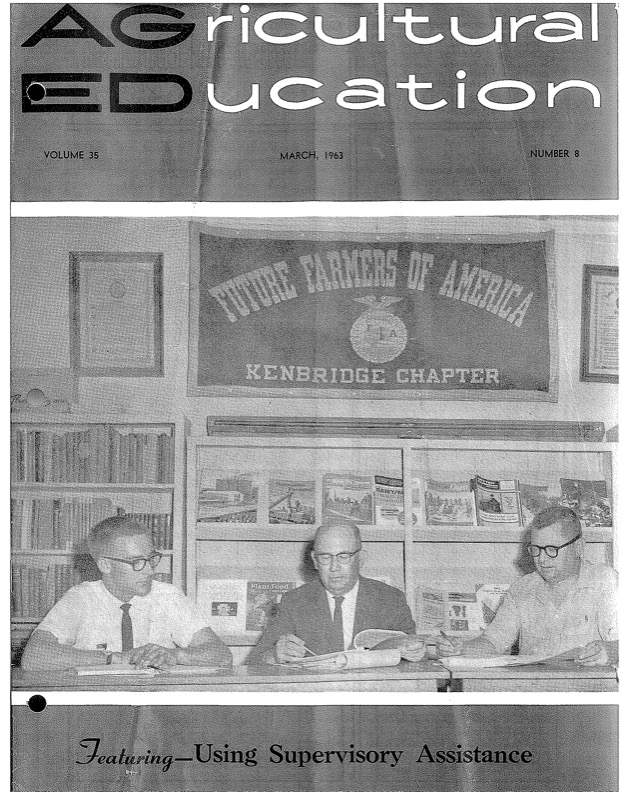

How did this happen? In his March 1963 article, “The National Center — A New Resource for the Profession” in The Agricultural Education Magazine, Taylor wrote:

A center which would provide advanced training and research opportunities for leaders and those preparing for leadership positions … has long been the hope of many. In 1959 the National Conference of Head State Supervisors and Head Teacher Trainers formally recommended … (exploring) the feasibility of … establishing (such) a center.

As a state supervisor in Arizona, Taylor would have been part of, perhaps even launched, this discussion. In the magazine, he further wrote,

… the U. S. Office of Education, with the assistance of (a committee of the American Vocational Association) and others, formulated a tentative proposal for the establishment of this center. This proposal and subsequent revisions were discussed at the American Vocational Association meetings and at the four regional conferences in agricultural education for two consecutive years.

And who presented the proposal at some of those regional conferences? Taylor. Who wrote more articles in association magazines about the idea and spoke at more conferences about it? Networked about it with faculty at other universities? Again, Taylor.

His voice was heard at national and statewide conferences. He shared the vision of the center while serving on national committees.

Phases Two and Three: Supporting all of vocational education nationwide

Having created a national agricultural center, Taylor then networked with state vocational directors and their federal legislative contacts to broaden his center’s scope. The result: in 1965, Ohio State won major funding from the U.S. Office of Education for the Center for Vocational and Technical Education.

“Bob Taylor was respected nationally,” said Darrell Parks, the retired state director of Career and Technical Education, Ohio Department of Education. “He was called upon frequently in terms of certain issues or concerns about vocational education and the direction that it should take.”

Taylor and Parks worked together in their leadership roles. They supported the establishment of joint vocational centers throughout Ohio. These schools served several school districts since no one district could afford to teach all the skills areas needed. The pair helped grow vocational education statewide.

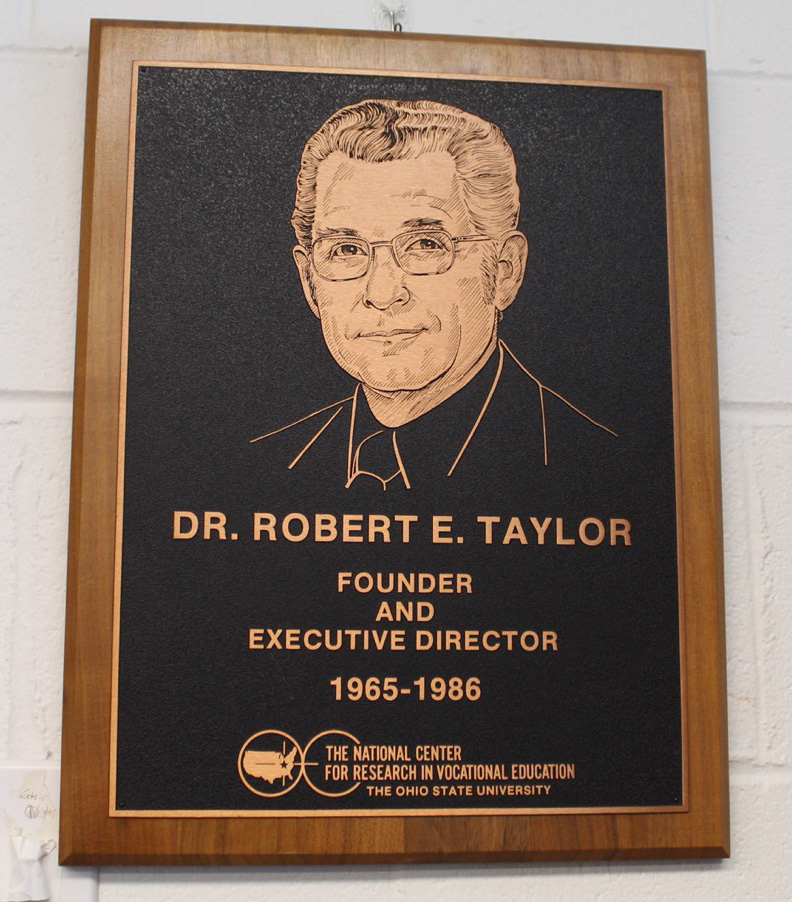

By the late 1970s, Taylor’s relationships in Washington, D.C., had evolved. He achieved his ultimate goal in 1977 when Ohio State received a contract to operate the National Center for Research in Vocational Education. Taylor, as director, managed a $4.5 million per year, five-year contract, which was renewed a second time in 1983.

“His middle name is ‘vocational education” suggested a 1978 article headline in the onCampus Today newspaper.

The charismatic Taylor also influenced having the national center’s authorization written into the Education Amendments of 1976, or Public Law 94-482.

Per The Ohio State University Annual Report for 1977-78: “This was the largest dollar-volume annual contract in the University’s history and the largest single contract ever awarded by the Office of Education.”

Achievements and accolades accrue

Frederick Cyphert, dean of the College of Education, was one of two Ohio State leaders who made Taylor an associate dean in 1974.

“Because of his insight, dedication and energy, the national center is a unique, one-of-a-kind organization,” Cyphert said in the onCampus Today article. Since its inception, the article continued, the national center has assisted agencies, institutions and organizations in solving the educational problems related to helping individuals prepare for and progress in jobs.

Taylor also served as an associate dean in the College of Agriculture and Home Economics. His leadership in the two colleges helped make Ohio State No. 1 in vocational education graduate programs for years, as ranked by U.S. News and World Report.

At the height of its operation, the center employed “about 225 people, has been awarded more than $128 million in grants and contracts, has held more than 1,000 conferences and completed nearly 800 major research and development projects,” according to a 1986 onCampus article.

Among the many notable achievements under Taylor, in 1967, the center established the Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC) on Adult, Career and Vocational Education. Added to the existing ERIC system, it collected research journal articles and publications from across the country.

In 1971, Taylor’s center was selected by the U.S. Office of Education to create the school-based national Comprehensive Career Education Model. It demonstrated how to integrate career education starting with career awareness at the youngest grades. Its model curriculum showed how to include career exploration in the middle school years. Field tested and revised throughout, it culminated with vocational preparation in high school.

“It was clear that Bob had strong relationships with the state directors of career and technical education and with key CTE leaders,” said Floyd McKinney, a senior research specialist who joined the center early in the first contract. “He was good at determining which state directors had influence with federal officials.”

“He, in collaboration with OSU leaders, worked hard with national Congress persons and their staff to be sure they were informed and could support his efforts to improve CTE programs across the nation.”

Taylor took early retirement in 1986. Without his charismatic leadership, the activities of the national center were split among several universities. One of those activities, dissemination, did return to Ohio State from 1998-2002.

Today, the college’s Center on Education and Training for Employment carries the banner first hoisted on high by Taylor. It is known for translating research into practices that address societal problems.

One grant project, the Ohio Statewide Family Engagement Center, helps educators and families work together to support children’s academic success.

The center has long been known for its many services, including its programs that develop curriculum, instruction and systems to support adult learning.

The DACUM (Developing a Curriculum) International Training Center, as one example, offers an effective method for analyzing jobs and occupations. It has been used worldwide for more than 40 years and in over 58 countries. Governments, industries and trade associations find it provides a solid basis for training curricula.

The dynamic center, begun at Ohio State by Robert E. Taylor, continues to evolve to meet ever-changing needs.