When the late alumna and Faculty Emerita M. Eloise Green began teaching nutrition in 1939, the discovery of vitamins was still fairly new. Not much was known about their role in human health. The Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act had just been passed in 1938 to identify additives such as artificial flavorings and preservatives.

Green saw many changes in society and her teaching during her 33-year tenure. Hired by Faith Lanman (later Gorrell), chair of the Department of Home Economics, Green’s appointment was 100% teaching.

“She loved that aspect of her work and was constantly working on improving the content and presentation of her courses,” said alumna and Faculty Emerita Fern Hunt. “She was a meticulous writer. I appreciated that especially when she advised me on my (master’s) thesis writing.”

Green was also well known to many. “Everyone who went through home economics had Dr. Green, I think,” Hunt said, “because food was one of the core courses.”

At age 98, Green reminisced with Hunt in a 2002 oral history about her time on campus.

The path to Ohio State and home economics

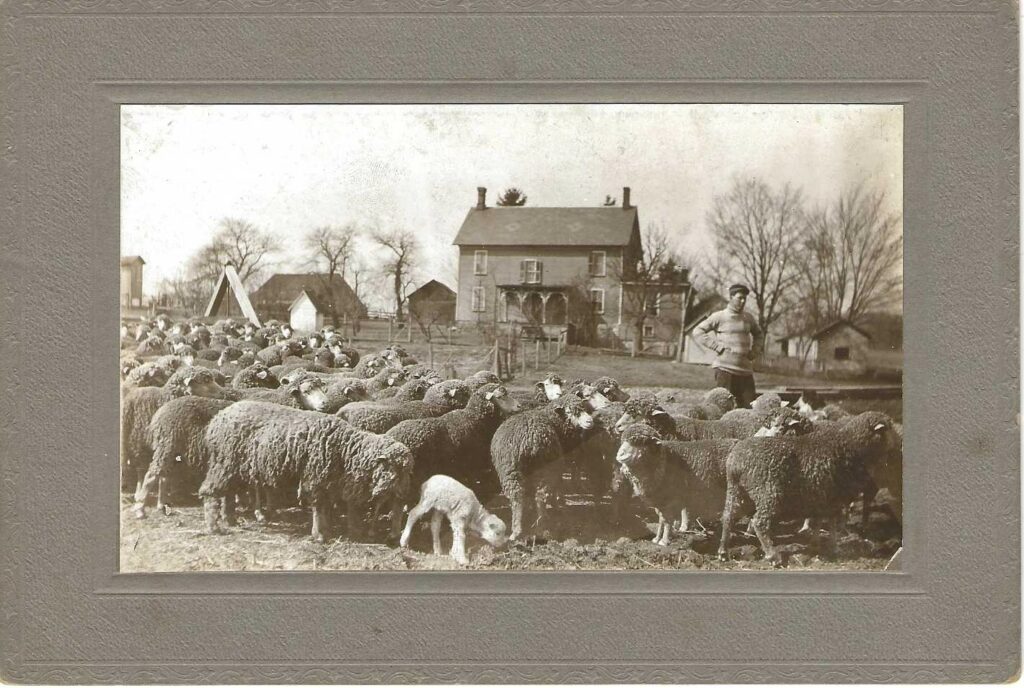

Although Green grew up on a farm near East Liberty in Logan County, her family encouraged her to attend college. She spent her freshman year at Ohio Wesleyan, then borrowed money for her sophomore year at Ohio State. By the end of the year, her funds had run out.

“At that time, it was possible, if you had two years of college, to take a state examination,” she said. “If you could pass that, then you could be certified to teach,” she said.

She spent three years teaching fourth and fifth grade at Perry Township School in East Liberty. It took that long to pay back the loan.

She then returned to Ohio State, where her older brother Earle also was a student. She learned that she had more than one choice for how to earn a bachelor’s degree and still teach home economics.

“I finally chose to get my degree in the College of Education rather than in the College of Agriculture,” she said. This was because the home economics students spent summers guiding high school student projects. Green, instead, spent her summers taking education courses to earn her degree sooner.

By that time, her father had died, and she needed to support herself and her education. So, she found a job waitressing at the Faculty Club, then in Bricker Hall. “I learned so much about food and food service,” Green said. “Since I eventually decided to major (for a master’s) in foods and nutrition, the training I got there was invaluable. …”

With her bachelor’s degree, Green taught high school for nine years. She lived with her grandparents, some miles from the school. The forward-thinking Green “purchased an automobile – the first automobile I ever owned,” she said. “It was a Model T Ford, and I drove it to school.”

She taught home economics but also science, which she had enjoyed at Ohio State. During summers, she worked toward her master’s degree, earning it in 1933.

When an opening occurred at Ohio State, Lanman hired her, a common practice to hire a program’s graduates then. “Not only did they know what they could do,” Green said, “but in general they felt acquainted with them and were pleased.”

On the faculty, innovations under the first director

In her first year at what was then the School of Home Economics, Green was an instructor, teaching the first foods course with her former advisor, Osee Hughes.

“We required the women students to wear a white uniform (in the food lab),” she said, “and of course the instructor wore a white uniform. Men wore a white shirt and no coat. … We also didn’t have paper towels, so each student had a cotton hand towel. You either pinned it to your belt or fastened it in some way. … The hair net for women.”

Green said Lanman created a laboratory for institution management, which was food service or what is now called hospitality management.

“It started out as a cafeteria on the first floor at the north end of Campbell Hall,” she said, “but when Pomerene (Hall) was built, part of it became Pomerene Refectory, and served not only as a laboratory but an eating place for students and faculty on the campus.”

During this era, new discoveries about food and nutrition were introduced into the university curriculum. Green absorbed and taught it all.

About all we knew of the makeup of food, she said, was that it had protein, carbohydrates, fats and minerals. “We would have such names as gelatin in meat, gluten in flour or albumin in eggs.” But complex food chemistry came later.

Green learned and taught a host of new information as discoveries were made. “For example, with protein, we began to know that they were composed of amino acids,” she said. “So, we had terms like tryptophan and phenylalanine and glycine. We knew that some of these amino acids couldn’t be produced by the body and had to be obtained from the food.”

In her oral history, the 98-year-old Green had no difficulty rattling off a litany of technical terms and their food sources.

“Incidentally, I can remember the first vitamin I ever saw,” she said. “It was in 1937. I had gone to the University of Chicago for the summer. The instructor, Miss Halliday, came into the class, took a little vial of white substance out of her pocket and laid it on her desk and said, ‘This is vitamin C.’ … They could isolate vitamins from the source and have it in the pure form.”

World War II challenges

When radios became popular. Lanman started a program called “Homemakers Half Hour“ on WOSU radio. The program was part of Lanman’s interest in community service, especially during the war.

“I can remember preparing talks when it was known as ‘Hometime’” in 1944, Green said. “I would go out, … sit in my car … turn the radio on and listen to my own talk.”

Green also taught non-credit homemaker classes for the Red Cross. Certain foods became limited, so the emphasis was on how to use scarce resources wisely. And she taught home economics in the university’s twilight school. The program offered courses in the early evening for working women who supported their families while men were at war.

In 1944, Green wrote a chapter, “Purchase and Selection of Food,” in the book Consumer Problems in Wartime, by Kenneth Dameron.

Post-war changes

Gladys Branegan became director in 1945, when Lanman Gorrell returned to the faculty. One of Branagan’s first accomplishments, Green said, was to establish the Home Economics Alumni Society and Alumni Placement Office. Both thrive today as the College of Education and Human Ecology Alumni Society and the Office of Career Development.

Always active in her profession, Green served as treasurer of the Ohio Home Economics Association and a member of its Executive Council. The Red Cross Nutrition Committee benefitted from her support as the representative from the School of Home Economics. She earned the title of assistant professor in 1946.

“Branegan also was noted for encouraging faculty to work for higher degrees,” Green said. “She was interested in building up the faculty … She was the one that encouraged me to take a leave of absence and earn a PhD.”

So, Green went to Iowa State College (now University) and held a research fellowship with the Iowa Agricultural Experimental Station while studying. She then was among 14 faculty with PhDs in the Ohio State school. The number had grown from two when Branegan started, which strengthened the graduate program.

Serving under a third School of Home Economics director

Dorothy D. Scott arrived as director in 1955. “She reappraised the curriculum,” Green said. “She introduced the honors program … She encouraged graduate study. She worked for improvement of the physical facilities.”

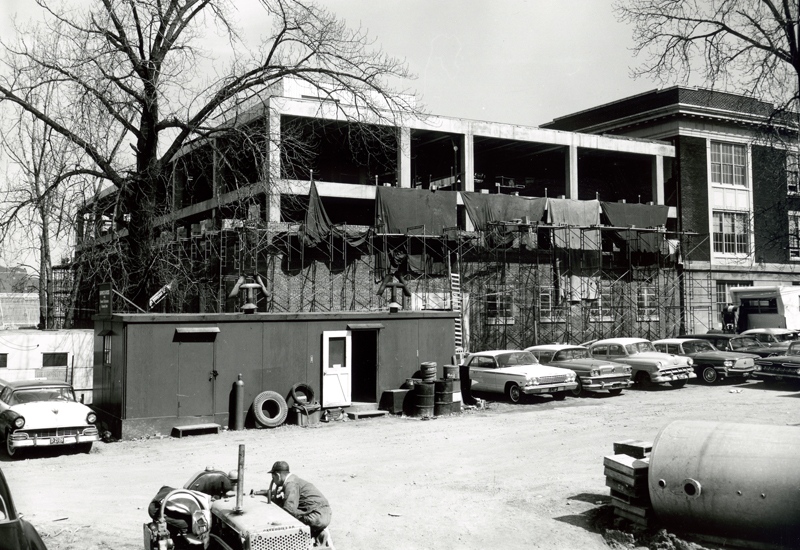

From her efforts, Campbell Hall gained a four-story addition. It provided additional office space, research laboratory space and more classrooms. Previously, Green had shared an office with four or five other faculty with one telephone among them.

Now she had a private office and her own telephone, a luxury.

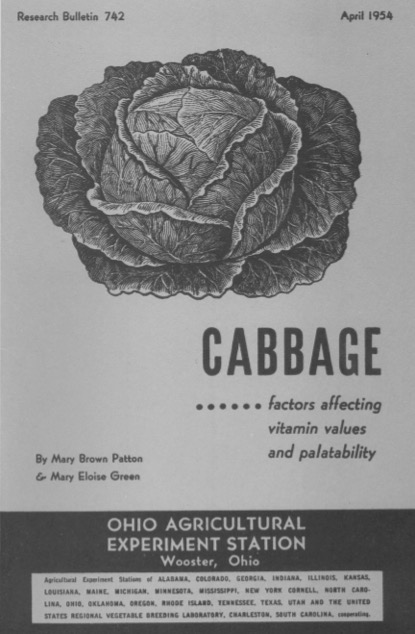

Green needed publications, so she wrote a series of bulletins for the Ohio Agricultural Experiment Station with colleague Mary Brown Patton. One, from 1954, explored “Cabbage: Factors Affecting Vitamin Values and Palatability.”

A doctorate allowed Green to advise graduate students. Faculty Emerita Fern Hunt was her first master’s advisee. For her thesis, Hunt said she studied whether the new commercial process of producing butter, called continuous churning, changed cake texture versus the former process.

Green was promoted to associate professor in 1955. In 1967, having taught for 18 years, she was named a Fellow in the American Association for the Advancement of Science, a prestigious achievement. She attained full professorship a year later.

Green served under her final school director, Lois Lund, in 1969. In 1970, Green was honored in a ceremony with Ohio State’s Alfred S. Wright Award for service to student organizations. She retired in 1972.

The Home Economics Alumni Association awarded Green its 1979 Distinguished Service to Home Economics Award. The honor recognized her expertise in laws regulating food preparation and packaging and the incorporation of that new knowledge into her teaching.

When Green turned 100, David W. Andrews, then dean of what had become the College of Human Ecology, wrote her a congratulatory letter to celebrate. She died in 2005 at the age of 102.