Best practices and rich cultural heritages blend to overcome life’s challenges

In America, children are considered our future. Yet, the number living in poverty remains stubbornly high. Overall, the U.S. population is 23% children, but they make up a third of all people living in poverty, according to the National Center for Children in Poverty. Unemployment is down, the economy is gaining, yet the young are less likely to benefit.

The college and alumni always have focused on improving the lives of children. They know all too well how poverty harms.

“Children living in poverty are at increased risk of exposure to violence and other life stressors,” said Antoinette Miranda, professor of school psychology. “Research clearly shows a strong link between the trauma and neglect that students experience and their mental health, which may lead to academic and behavioral challenges in school.”

Compounding the poverty, a growing number of children nationwide enter school unable to speak English.

Nearly 26% of U.S. public school students were Hispanic and learning English in 2015 (National Center for Education Statistics). The Ohio Department of Education says nearly 40,000 of the state’s public school students spoke limited English in 2010. That’s 199% more than in 2000.

“Yet Ohio is hampered by being behind other states with well-established dual language education programs,” said Peter Sayer, associate professor of foreign, second and multilingual language education. Still, the value of learning two languages is irrefutable. “Research shows if you have a really strong literacy program in the first language, it produces better results in the second

language as well,” he said.

Recent U.S. Census data shows Ohio benefits from the influx of people from other countries and states. If not for these arrivals, the state’s population would decline. And a decrease in population can translate into a slowing

economy.

The EHE-school partnership

Principal Katy Donovan Myers, ’98 MA, at the K-6 Columbus Spanish Immersion Academy, faces the reality of these statistics every day in the Columbus City Schools District.

“Some of our students are dealing with circumstances beyond their control,” she said. “Parents may be in prison or have died.”

“We see students losing control of their emotions and melting down,” said Bradley Havelka, ’12 MA, ’14 EdS, the school psychologist at the academy. “They’re reacting to things in their lives, not the small incident that just happened.”

Myers doesn’t flinch when faced by these daunting issues. Not when, within a month of her 2014 start as principal, the state put the school in “focus status.” Not when she learned what focus status meant: at least two subgroups — in this case, Latinx and English Language Learner students — were performing well below the state average in literacy and math.

“Within weeks of my arrival, the college’s faculty was knocking at my door, offering to help,” Myers said. Looking at the school’s report cards together, they found that when the school started in 1987, no students were English language learners. “We were just teaching people how to speak Spanish.”

Year by year, the school population changed. By 2011, nearly 40% of the students were Latinx.

“All these years, the school did not have an English as a Second Language program,” Myers said. “Our Latinx and ELL populations couldn’t pass the state’s tests in reading and math.”

So she and the college partnered. Together, they found solutions.

Embracing a brave, new world

Today, the academy has roughly 45% Latinx students, 45% African American. The rest are white or Asian. Myers and her team believe every student brings a rich cultural heritage to school. Cross-cultural relationships and learning are invaluable, they said.

While the whole school studies and honors Spanish-speaking countries and ends each year with a cultural fiesta, the African American community plays an equal role in sharing its unique experiences.

Building on the value children bring to school, the educators offer many services. They work a sophisticated system to support children’s mental health. They guide them in learning Spanish and English, speaking both languages interchangeably.

Carol Ann Mira, the English as a Second Language teacher, runs a pullout group for the academy’s newcomers. Anyi Palma Martinez came from Mexico. She knew little English before starting the 2018 school year. But she gestured with enthusiasm during discussion, her interest in learning clear.

Victoria Reyes Marquez, from Venezuela, spent a year at another Columbus school before joining the academy in August 2018.

Mira, ’96 MA, guided the girls through the plot of an English picture book. Anyi spoke mostly Spanish; Victoria now spoke English with ease.

The girls read aloud and answered questions, sometimes choosing new vocabulary from a chart. Both switched fluidly from English to Spanish and back again, known as translanguaging or code-switching.

“Teaching a dual language education program isn’t easy, especially because Ohio’s standards and testing are all in English,” Sayer said. “This pulls you away from the minority language,

so it’s tricky to maximize opportunities for students to practice both languages.”

Ohio also is behind other states in creating model dual language education programs that meet the needs of its unique population. To help create a program, Sayer and graduate research associate Melissa Adams Corral have listened to teachers’ needs and provided professional development in response to their vision for their school. He also sat in on leadership team meetings to gain more insights.

Complex decisions must be made. Many Latinx students at the academy are native Spanish speakers, but some are dominant English speakers. Their families want them to develop their heritage language while learning English. Other students spoke no Spanish at first, but their parents understand the value of a second language.

“It’s figuring out the linguistic diversity within each classroom, then understanding how to integrate strategies into an instructional unit,” Sayer said, “because there’s logic about how to build those rather than using them scattershot.”

In Mira’s classroom, Anyi seemed intrigued by English verbs. “What is the difference between roar and growl?” she asked in Spanish, even though “growl” was not in the book. Mira answered in Spanish but used English as well. She pointed to the open-mouthed lion roaring in the storybook and “roared” the word in English. She made a deep-throated sound for “growl.” Anyi nodded.

As they discussed how the lion is both angry and hungry, Victoria noted that both words end with the same letters.

“Victoria has improved seven levels in her English reading since the start of the school year with us,” Mira said. “That reflects two years of growth in under a year.”

Helping kids de-stress

Outside the principal’s office, a child stood before a set of wall signs. The title sign says “move.” She studied the choice of exercises, given in words and pictures on laminated sheets. She made 10 arm circles, then marched in place 10 steps.

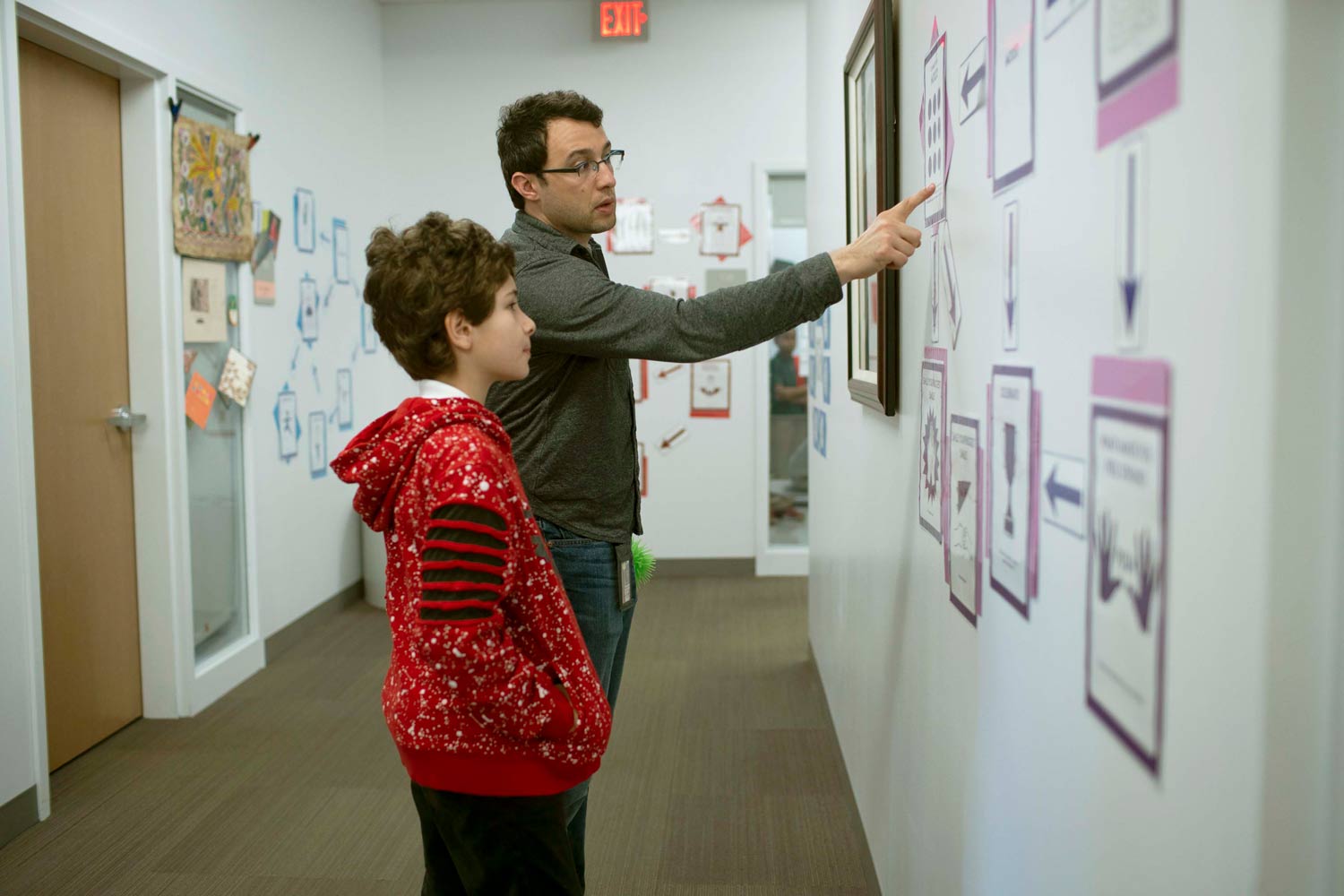

“What are you doing?” asked Sayer, who had finished his work and was waiting to pick up his third-grade son, who attends the school.

“I’m taking a brain break. I didn’t have to. I did all my work,” she hastily added. “I just wanted to.” She went next to a station labeled “recharge” and tried the tree, one of six yoga poses.

All the academy children know if they feel stressed, they can take a brain break. Teachers can ask kids to take one, too.

Havelka started the brain breaks at the school. Because the need for mental health support is high, he partnered with Antoinette Miranda, whose school psychology graduate students spend a year gaining required experience at the Spanish Immersion Academy or Ohio Avenue Elementary School.

The graduate students created the content for the three brain break stations. They conducted wellness activities for teachers to help them manage the stress of working with children experiencing trauma. They also offered counseling to children, in groups and individually.

“We made a conscious effort to ask the academy what they needed,” said Miranda, also the Casto Professor in Interprofessional Education.

“We’re now part of their Multi-Tiered Systems of Support,” Miranda said. If our students provide mental health services, they’re acknowledged as if they are staff.

If a child is on the verge of a meltdown, Havelka doesn’t try to address the issue in the classroom. “We go to the gym or other space so they can de-escalate,” he said. “Physical activity, especially if it calls for hand-eye coordination, calms a person down within minutes. We throw a ball back and forth. They jump rope. Then they slowly begin to talk.”

Havelka considers the school’s system of supports sophisticated. “We put the students in charge by inviting them to choose from a selection of self-regulation activities. It’s a plan in place especially for them.”

Counseling gets at issues, increases social comfort

Five sixth-grade boys, all lanky limbs and rowdy grins, gathered around a table in a small conference room. Their exuberance filled the air, cut by a hint of pre-teen angst.

School psychology PhD student John Jinsoo Park initiated this counseling group in the last year.

“I’ll ask the group, ‘Why are we not doing our homework?’” Park said. “There will be quiet at first. One kid, who is braver, admits that it’s Fortnite. That’s when the room explodes. Everyone goes around sharing how many wins they’ve had.”

Once the boys open up, real issues get addressed. “We have an anxiety thermometer,” Park said. It goes from one to 10, with 10 being the most anxious. “We ask them, what is your level of anxiety about speaking Spanish in class? They (the Spanish-speakers) answer zero, one, two tops.”

“But when asked, ‘What is your level of anxiety about speaking in English?’ then you get five, six, seven,” he said.

For teachers, Havelka and the college students held weekly sessions to discuss concerns about students.

“We addressed both academic and behavioral issues,” Park said. “If a concern is behavior, the discussion involves possible triggers. We come up with a unique plan, offering the student a

replacement behavior and reward for using it.”

Reading, math scores improve

Myers is proud that, since working with Sayer and other college faculty, she led her school out of focus status as of the 2018-19 school year. The students improved in literacy and grew two levels in math.

Sayer said their work together has provided a successful model for dual language education programs in Columbus City Schools. He and other college faculty are collaborating with the district to open a new magnet middle school where students can continue their language tracks. It will support creation of a model dual language education program for grades 6-8.

The Columbus Spanish Immersion Academy shows how urban America’s schools and children’s needs are not the same as they were 20 or even 10 years ago. Each school may be different, with many shades of diversity. Teachers and school leaders must be nimble to respond.

Dean Don Pope-Davis is leading the college to expand its collaborations with not just this school, but with districts and communities across the state. He has appointed three superintendents in residence to serve the college, one each from a rural, urban and suburban district. They will work part time, representing and teaching about the needs and interests of learners from different areas.

A collaboration with the Columbus Urban League and other organizations will place the college’s new postdoctoral researchers in community offices. They will coordinate the work of faculty, staff and students, who will offer services such as tutoring. In the process, they will earn trust and discover new ways to collaborate.

All these interventions, engineered by the college with its many partners, reflect the belief that urban schools and communities can be places of promise that foster growth and development for all youth.