The whiplash of the COVID-19 pandemic and racial injustice in America has unleashed a peculiar kind of chaos on teachers and school administrators.

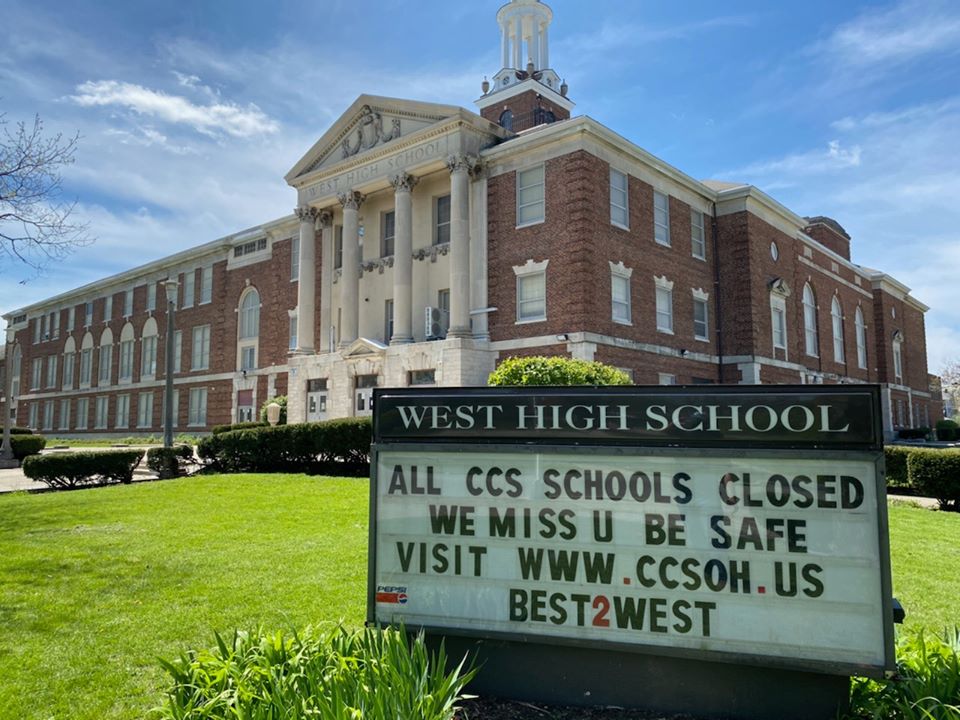

As school buildings closed in March with little notice, disturbing inequities in student resources came to the forefront. Teachers pivoted to provide remote instruction — “building the airplane as we jumped off the cliff,” one college alumna said.

“Teachers like to have control; this just threw all of that out the window,” said Sarah Thornburg, MA ’01, a humanities teacher at Columbus Alternative High School. As weeks dragged into months, students wanted to know when normal times would return. “You’re the one who’s supposed to have some answers. It’s super frustrating not having anything to tell them. That’s your job. We couldn’t do it.”

Teachers and administrators drilled down to fill gaps, assess needs, adjust to surreal circumstances. Then, just as school wound down, communities erupted after a Black man named George Floyd was killed by police in Minneapolis. Teachers watched via newscasts and social media as their students protested.

“I feel this intense responsibility to make sure they know I’m very proud of them and I’m glad that they’re out there…. but please tell me that you took a mask,” Thornburg said. “The mom in me comes out.”

As districts began a new year — many exclusively online — teachers longed for brick-and-mortar classrooms yet fear for their safety. The expectation that teachers must be safety advocate, counselor, technology wiz, ally for racial equity — working masked or remotely, and often at the same time overseeing their own children’s learning — has been a herculean lift.

And yet many EHE alumni are meeting the task head on. The college has stepped forward with science-based guidance, professional training and critical reopening assistance.

Never before has education been so necessary and yet so difficult to deliver. On the roller-coaster ride that is American education today, our experts and alumni are forging paths to find better outcomes for children.

Getting up to speed, equitably

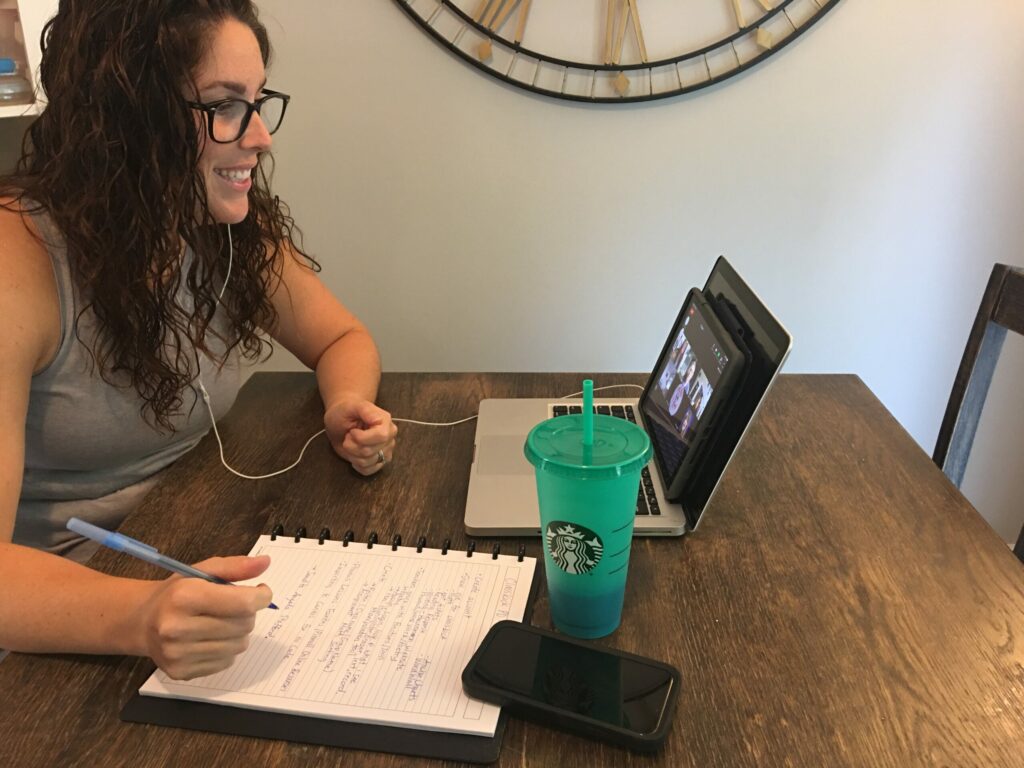

Ellen Harpham, MA ’01, became acutely aware of limits to a 6-year-old’s attention span in March, when she used Zoom to instruct her first-graders from Beacon Elementary in Hilliard. A fishbowl in the background could derail the lesson.

“It would be, ‘Oh, you have a fish?’ ‘I have a fish!’ ‘I have a dog!’ ‘You want to see my cat?’ We saw everybody’s pets. It was comical in some ways,” she said. “It was also very frustrating.”

Harpham’s students were better off than others. Hilliard has been a one-to-one district — one iPad per student — for 10 years. Before schools closed in March, student teacher Katie Konrad, BS ’20, had taught first-graders in Harpham’s class how to upload videos and assignments to Google Drive.

Many urban and rural students had no such point of reference. Without tablets, Wi-Fi access or public libraries, online learning was a no-go for many kids.

For Columbus Schools, it took a pandemic to fix what should have been done years ago, Superintendent Talisa Dixon said. Her district received $7 million in CARES Act funds from the city to buy 20,000 Chromebooks, which together with existing computers are allowing remote learning. Donated and purchased hotspots provide Wi-Fi access.

“I needed to push the district forward faster,” Dixon said during Back-to-School Perspectives: Leadership through COVID, one of three forums hosted by the college this summer. “It allowed me to say…‘We’ve got to think about the future and how we need our students to use technology as a lever.’ Because of these unfortunate circumstances, we are here now.”

It’s one of numerous knots that needed untangling to get schools up and running again. Collaboration — with the city, donors, colleagues and the university — is getting the job done.

After securing funding for the tablets, the first person Dixon called was Hilliard City Schools Superintendent John Marschhausen. He, Dixon and Marie Ward of the Fairfield County Educational Service Center serve as the college’s superintendents-in-residence, a leadership program initiated by Dean Don Pope-Davis in 2019 to foster deeper collaboration among districts and the college.

Dixon knew Marschhausen is ed-tech savvy.

She said, “’John,…What are you doing? How did you get there? What platforms are you using?’ We just bounce so many things off of one another and that has helped us.”

The college also provided direct assistance. After Hilliard and Columbus drafted initial reopening plans, the college’s K-12 Reopening Task Force reviewed their policies. The 25-member team offered expert advice, from deciphering data to emphasizing how art and music instruction helps reduce student stress.

We’ve got to get our staff ready to have these conversations, and it doesn’t matter the grade level or the subject. If a kid in one of those morning meetings wants to talk about what it’s like to be Black in Hilliard, and what they felt this summer, we’ve got to be ready.

John Marschhausen

Teaching social emotional learning

Sarah Thornburg and her Columbus Alternative High School team tackled remote teaching in March with gusto.

“We were like, let’s go. We found out, not only could we not teach the way that we wanted to, but we shouldn’t,” she said. “Everything had to slow down and focus not on content but on their mental well-being.”

Some students doubled work hours to help pay bills. Others were in dire financial straits because family businesses shut down overnight. Some living with grandparents were terrified.

“They were worried that they were essentially going to kill their grandparents. That’s a burden that’s incredible for anybody to have, much less for a 15-year-old to deal with,” Thornburg said. “You can’t teach a child who’s completely freaking out about, ‘Are we going to lose our home?’ That was eye-opening … I don’t know that any of us were prepared for that.”

Fear and anger about violence against Black Americans intensified the anxiety. Students may not have an outlet for those fears, Marschhausen said during the forum.

“We’ve got to get our staff ready to have these conversations, and it doesn’t matter the grade level or the subject. If a kid in one of those morning meetings wants to talk about what it’s like to be Black in Hilliard, and what they felt this summer, we’ve got to be ready,” he said.

Responding to the need, the college’s Racial Justice and Equity Task Force developed a learning module on implicit and institutional bias tailored to K-12 educators. Building on content from the Kirwan Institute, the training helps educators examine racism and bias in schools. Thousands of teachers and staff from Columbus, Hilliard, South-Western, Westerville, Bexley and Reynoldsburg districts participated; the training is now available to other districts.

EHE Task Force experts stress making student engagement a priority when students are learning online. A new study by Associate Professor Tzu-Jung Lin, professors Michael Glassman and Eric Anderman will do just that, developing a social studies curriculum for remote and blended learning that fosters discussion and deepens elementary students’ understanding of complex civic issues.

Other districts are hosting virtual morning meetings using break-out rooms in Google Meet and Zoom, allowing critical small-group discussions, even among very young students. Allowing students to spend non-instructional time together online makes it easier to forge personal connections, professors Eric Anderman and Kui Xie wrote in August.

Expanded professional development — which thanks to COVID-19 has blossomed online — trained teachers about social emotional learning and remote teaching. Other research interprets data specific to schools to ensure students’ social emotional adjustment. Such research and instruction are critical to leveling the deep furrows that the crises have created in education.

How to teach remotely

Almost no research exists on how to best teach children remotely — primarily because experts firmly believe most children learn better in person. But studies about teaching adults online offer clues.

Weaving curriculum into activities that interest children — and offering online assets to underscore learning — gets the job done. For Ellen Harpham’s distracted first-graders, Pet Week was born as students’ unleashed their enthusiasm writing and creating videos about animals.

Mark Frank, MA ’09, led his Bexley Middle School algebra students to work in teams designing roller coasters using piecewise functions and online graphing software. The project was modeled on one he supervised for years.

“Student submissions were still wonderful, creative and interesting,” Frank said. “And they were even more impressive given how students needed to remotely collaborate.”

Deep learning can happen at even young ages if you pose the right questions, said Theodore Chao, associate professor of STEM education. When his three children were 3, 5 and 7, he asked them when their ages would be all prime numbers again. They’ve had a running math lesson ever since. That inquiry-based learning meshes well with online instruction; the web is filled with ideas for teaching it.

“Instead of telling a student what to do and having (them) memorize things, open up with a really deep inquiry-oriented question, and then have them figure it out and explore it,” Chao said.

The approach takes the focus off the teacher and puts it on the learner; college research shows it builds intrinsic motivation among learners.

For lessons requiring teacher input, alumni use a plethora of online tools. Megan Norris, BS ’14 and a current master’s student, used free tools to create such compelling instructional videos for her first-graders that her district asked her to lead two summer professional development sessions.

Norris’ new Instagram page linking to her YouTube videos — The How-To Teacher — netted 138 followers its first day.

She’s big on teaching kids using leadership guru Tim Kight’s Focus 3: Event + reaction = outcome. Their outcome is “growing your brain,” she tells them, “so how will you react to this event? Use your iPad? Work with a friend?”

It works for adults, too: Their event is COVID-19.

“The outcome is we’re still teaching,” she said. “So, what is your reaction? Well my reaction is, I’m going to learn new things because that’s the only way my kids are going to stay engaged.”

“We still want them to love school. We’ve got to bring what we can to the table for them to know, ‘Hey, we’re learning, we’re having fun, we get to see our friends. It just looks a little different.’”

Major crises have always driven great change. Why not harness this one?

“I think this is an opportunity to reimagine the education space,” Dixon said. “We should be forward thinking. We should be partnering with colleges like we are, and really thinking that when this deadly, ugly virus is over, our schools are going to look so different.”

It’s time to “get out of the box,” she said, and transform our schools for the better.