Sarah Morbitzer earned a BS in exercise science this past summer and is a prime candidate to pursue her dream of becoming a pediatric cardiologist. To get there, determination has marked her character throughout her life.

That resolve came to the forefront when she was a freshman. As a new player on the Ohio State Women’s volleyball team, she experienced unusual pain and shortness of breath one day during practice.

“I wasn’t able to keep up with all the reps of conditioning or do the sprints,” she said. “I was a walk-on, and it felt like I was just getting to my dream (to be a college volleyball player), and it was all being taken away.”

She recognized the frightening reality at once. Her chronic heart condition – she’d undergone surgery to repair it when only four months old – had returned. It could potentially stop her cold in her game.

Morbitzer had been raised on a diet of volleyball. Her math teacher and volleyball coach mom, Carole Morbitzer (’95 BS math education), took her daughter to practice regularly.

“I remember her telling me that when I was a baby, she would push me around in the ball cart, would put me in a corner (to watch) with my Cheerios,” Sarah Morbitzer said. “As the girls were serving and spiking the ball, if they passed me, they’d make sure I had my Cheerios.”

“As I got older, after school, my dad (Mike Morbitzer, ’95 BS English education) would pick me up, take me to Mom’s practice. So, I ended up growing up in the gym.”

Morbitzer loved her Mom’s players. She looked up to them and was determined to be just like them. “It also built such a great relationship with my mom,” she said. “We’re so close because of it. VolIeyball has been helpful in my life in more ways than one.”

Playing club volleyball throughout school cemented Morbitzer’s love of the sport. “I played on my first club team when I was eight,” she said. She moved through as many as 12 teams as her skills developed. “My mom had a small club of her own, but I ended up passing that level, too. So, I played with Mintonette Sports. It’s a very good club.”

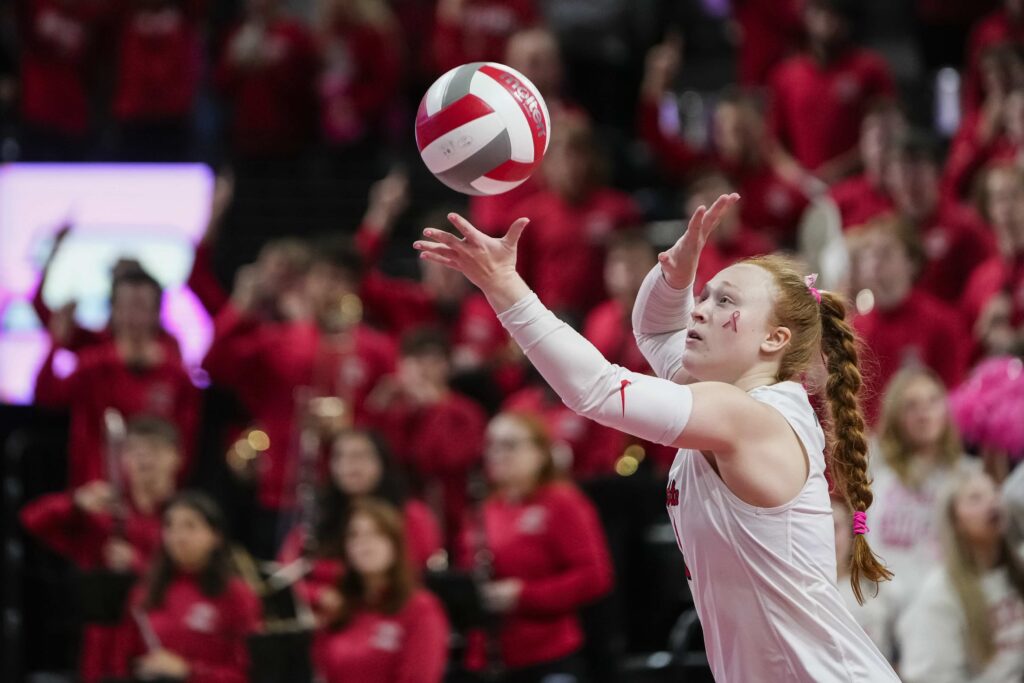

As a freshman, Morbitzer earned a place on the Ohio State Women’s volleyball team. But she wanted to move beyond being a walk-on. She wanted to be a scholarship player, paid to play. But as her first semester dragged on — a COVID-19 autumn of no games, only conditioning — she knew.

“This was the moment my cardiologist had warned me about,” she said. “He always told me, ‘You’re going to know when it’s time for your next procedure.’”

Unique choice leads to a promising future

True to her determined nature, Morbitzer chose a clinical trial to dodge open-heart surgery and a six-month recovery. The alternative procedure involved a minimally invasive heart catheter and the hope of returning to play in record time.

Her parents were nervous: Clinical trials are for testing new procedures. Was this going to be safe?

“I think it was the fiery redhead in me that was like, “No, we’re doing this,” she said. “I’m very thankful that they allowed me to pick what I wanted.”

Sure enough, she started for the Buckeyes in a match a mere month later. She was still a freshman.

During spring semester of her sophomore year, a heart-warming announcement at a team meeting left Morbitzer speechless. Her coach shared that Morbitzer would have a coveted athletic scholarship to play for the rest of her undergraduate career. Her teammates crowded in for a group hug.

“That was such a big day for me,” Morbitzer said. “Not everyone on a team has a scholarship. To start as a walk-on and end up getting a scholarship is huge and rare. It was so memorable.”

The perfect major for a pre-med athlete: Exercise science

What was the best major for an engaged scholar-athlete hoping to attend medical school? Becoming a physician requires prerequisite courses in science and math. The college’s Exercise Science Program offers exactly what is needed.

“I was really interested in sports and how the body moves, the mechanics of being an athlete,” Morbitzer said, “so exercise science seemed perfect for me.” She especially appreciated studying all aspects of health that contribute to athletic performance. “Things like nutrition and sleep are so important,” she said.

Because being a scholar-athlete is so time consuming, Morbitzer took all her major courses this past spring semester.

“In the lab portion of my courses, I learned how to run a stress test,” she said. “I’ve had at least 10 of those, so it was cool being on the other side of it for once, learning to manage the stress test environment.”

She also enjoyed being on the other side of an ECG or electrocardiogram, practicing on her fellow students. “I can’t count how many of those I’ve had,” she said. “In the labs, I learned how to place the stickers, how to read results. My classmates started learning about my heart condition and asked questions. So, I got to tell them a bit of my story and how what we were learning related to a real-world situation.”

Morbitzer especially enjoyed the small class size. “Because my labs had (an average of) 12 people in them, I got to know 12 non-volleyball people.”

One lab experience impressed on Morbitzer how she differed from those non-athletics colleagues. They were practicing being an exercise instructor, teaching a subject to lift a weight safely. “So, I was doing my lifts, and I remember I got up to 170 (pounds) or something,” she said.

Heads turned. Everything stopped. “What do you do outside of this class?” they asked, clearly dumbfounded.

For Morbitzer, lifting was a way of life. She and all her teammates did it. To her, her strength was normal.

“It was the first time I was able to see (others) appreciate the work I’d put in the last four years,” she said.

Next up: Applying her exercise science expertise

Morbitzer is taking a gap year before applying to medical school. She’s in patient nutrition at the Davis Heart and Lung Research Center, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, to gain more hands-on experience. She also coaches at the club that nurtured her skills as a youth — Mintonette Sports.

But whether she becomes a pediatric cardiologist or pursues another health-related career, Morbitzer said studying exercise science proved a good choice.

Another good choice was her minor, the college’s Human Development and Family Science Program. Considered an excellent background for going into medicine or family law, it taught Morbitzer how humans develop physically, emotionally and socially across the lifespan in the context of the family.

Thanks to her major, Morbitzer already knows how all the systems of the body work, all the mechanics, many of the health issues associated with the body and many relevant tests for them.

“Going into med school, it’s definitely going to help me,” she said. “Those classes really prepared me for the next step.”