Laura Justice gets books in the hands of Mexico’s kids in need

For years Mexico has been synonymous with endless beach coasts, clear-blue water and all-inclusive resorts — but there’s more to the country than meets the eye.

The majority of Mexico’s indigenous people — many living in Yucatán and surrounding areas — are impoverished. One-third of the native population is considered to be functionally illiterate.

For the Maya people (“Mayan” is often used, but “Maya” is actually the correct terminology) living in Yucatán’s rural communities, access to books is extremely limited. Most households — usually having at least three children — own no books. Even in government-supported preschools and childcare centers, young children have limited or no access to literacy materials.

Without books, children can’t learn the alphabet. They don’t discover a variety of words. No basic writing skills are developed. Ultimately, chances of future reading achievement are bleak.

But it hasn’t always been this way. Hailed as one of the most advanced cultures of all time, the Maya people have fascinated explorers and scholars for centuries. Their detailed sculptures and hieroglyphic script were spectacular.

Established in approximately 415 A.D., Chichén Itzá, now called Yucatán, thrived. It was once one of the largest and most sacred Maya cities. And then that all changed. To accelerate the spread of religion and colonialism in the 16th century, Fray Diego De Landa, a Spanish monk, demanded that all handmade Maya books be destroyed in the Yucatán region.

More than 400 years later, young children are still affected by De Landa’s decision.

Book, line and sinker

In 2009, Distinguished Professor of Teaching and Learning Laura Justice visited Merida, Yucatán’s capital city, on a whim. Because she is a speech language pathologist, a colleague asked her how she might help the children taking part in a local occupational therapy program.

In 2009, Distinguished Professor of Teaching and Learning Laura Justice visited Merida, Yucatán’s capital city, on a whim. Because she is a speech language pathologist, a colleague asked her how she might help the children taking part in a local occupational therapy program.

Researching young children’s developmental vulnerabilities in language and literacy acquisition is Justice’s passion, so it’s no surprise that she fell for the Yucatán children — book, line and sinker.

“Once I saw the work that this area needed, I knew I’d have to come back to help in the way that I wanted to,” said Justice, who also serves as the director of EHE’s Schoenbaum Family Center and the Crane Center for Early Childhood Research and Policy. She has returned to Yucatán regularly for seven years, introducing books into the state’s curriculum.

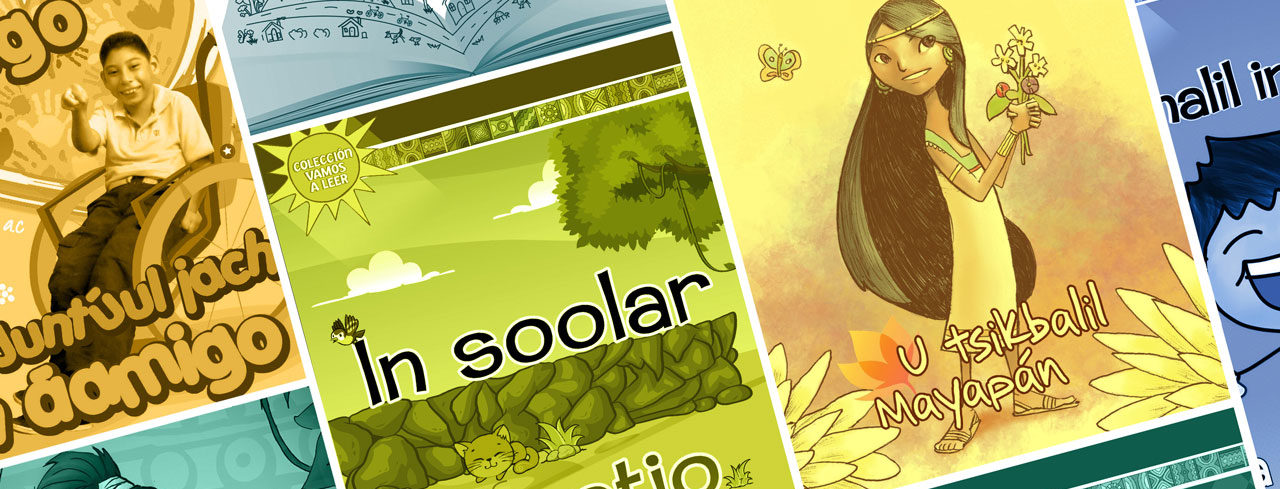

In 2015, Justice received funding from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation to create Solyluna Club de Lectura, also called “u kuchil xook kiin yéetel uj” in the area’s native Maya language. Club de Lectura provides a bilingual book collection to children, ages three to six, who speak both Maya and Spanish.

The books’ illustrators, who are from Yucatán villages, create visuals that help children relate to the short stories.

For once, these Yucatán children have books of their very own. The books are simple; most have only one or two words per page. But they’re making a difference. Many early literacy skills can be quickly improved by exposure to simple books. Justice has learned this firsthand.

“We saw their early literacy skills developing,” said Justice. “Their knowledge of print concepts, familiarity with the Maya and Spanish alphabets and their ability to write all improved.”

Parents complete the story

Last year, 148 Yucatán parents and caregivers attended four workshops to learn the best ways to read to their children.

Last year, 148 Yucatán parents and caregivers attended four workshops to learn the best ways to read to their children.

“It’s important to collaborate to make a better future for our children,” said Sasil Sanchez Chan, project director for Club de Lectura. As a native of the region, Sanchez Chan is also bilingual in Spanish and Maya.

To make Club de Lectura sustainable, Justice and her team educate local “mother trainers” to lead the interactive sessions with parents. Each culturally relevant workshop lasts about 40 minutes and has a specific focus. One session might tackle how to share a book with your child in an enjoyable way. Another shows how to play a literacy game to improve speaking skills.

This year, an additional grant from the Kellogg Foundation is allowing Justice’s parent-child literacy program to expand to 20 new villages in the next three years.

“Entering into this program, it was somewhat unclear whether parents would be interested,” said Justice. “We are so happy to find that their interest has far exceeded what we anticipated.”

With the community behind them, the program’s new goal is to reach 1,000 parents and children. Because few children’s books are available in Mexico, and virtually none are bilingual, Justice and her team are also creating 12 new books.

New community lending libraries were created to act as a shared space in the villages for all parents and children to focus on learning.

“The goal is to get books in the hands of young children,” Justice said. “Parents and lending libraries serve as a conduit to making that happen.”

Help the Solyluna Club de Lectura grow: Visit give.osu.edu/Mexico

Help the Solyluna Club de Lectura grow: Visit give.osu.edu/Mexico