Listen to the Inspire Podcast

Listen to Antoinette Miranda talk about advocating for children and the personal tragedy that led her to make change at Ohio State. The Inspire Podcast releases May 21.

Throughout her life and career, a distinct and yet unexpected pattern has connected the moments that have defined Antoinette Miranda. The woman who has been an Ohio State department chair, program chair, endowed professor, state school board member, school psychologist and mentor par excellence calls the phenomenon “the intertwining of things.”

To wit: At her first job after earning her PhD in school psychology from University of Cincinnati, Miranda’s supervisor in New York City Public Schools looked oddly familiar. Her first day, she went home and dug up a photo from a conference she attended four years earlier during grad school. There was Sharon Yoshida, her new supervisor, sitting among other school psychologists at a table with her.

“Think about that,” she said.

Miranda studied, taught and worked in school psychology for years — elevating culturally responsive behavioral interventions for general and special education students, including children with physical and learning disabilities — before having a child of her own who has disabilities, in 1993.

By then, she was pursuing tenure in her faculty position at Ohio State.

“I could not have been successful without Candace,” the nanny to Miranda’s children while she, an assistant professor, juggled grants, teaching, service and being a mother. Years later, it was Miranda who provided before- and after-school care for Candace’s kids, so the mother of three could pursue her own career.

“All these interconnections,” Miranda said. The intertwining.

Some believe there is no coincidence — that all the touchpoints come together if you will only recognize the convergence. Miranda lives life that way. Now set to retire from the College of Education and Human Ecology after 37 years at Ohio State, the full pattern of her connections is coming into focus.

A career entry moment meant to be

Miranda’s timing for entering the field of school psychology, like much of her career, was fortuitous. A new federal law — IDEA — mandated how school districts were to teach children with disabilities.

“I was really at the beginning of that law, which really helped explode school psychology because school psychologists are written into the law to do the cognitive assessment,” she said.

The Columbus native moved to New York with her fiancé before finishing her doctoral defense at University of Cincinnati in 1985. She was among a large contingent hired by New York City Public Schools that year. “(The district) actually was in the midst of a court case, because it was taking too long to do the evaluations,” she said. “So now I understood why, when I got hired, there were 250 of us.”

The setting was perfect for Miranda. “It was the kind of place that I had been reading about, studying about, learning about,” she said. “Now I got to witness it.”

“I wanted to be in a district where I was going to work with kids that may be in poverty, that were culturally diverse. Little did I know the whole district was in poverty.”

She collaborated with diverse colleagues, serving children in the margins who had learning disabilities and behavior management problems, needed to be mainstreamed or had fallen through the cracks.

“It put me on my path to Ohio State, what I did in the community and even eventually at the state (school) board,” to which she was elected twice in Ohio. “I had become really interested in students who were diverse and were not succeeding educationally.”

Miranda became keenly aware of how homelife, family culture, race, socioeconomic status and parental education impact any child.

“She was always very passionate about how to support students, how to ensure that we were doing the right thing for students, especially students of color,” said Anna Williams-Jones, MA ’89.

Miranda’s advisee in the college’s School Psychology program, Williams-Jones now directs special education for Marion County Public Schools in Florida.

A Latine child does not respond to a school setting exactly as a white child does or perceive a lesson the same way a Black or Asian child does.

“You’re looking to identify the needs of students educationally and ensure that you can support those,” Williams-Jones said. “But when you’re looking at students from different ethnic backgrounds, it adds an additional layer of protections that you need to consider to ensure that you are, in fact, meeting the needs of those students appropriately.”

“(Miranda) was instrumental in helping me to develop that lens for the work that we do.”

Coming back to Ohio

A flyer from Columbia University got Miranda thinking about teaching school psychology to graduate students. The week before she interviewed for that job, she bumped into Ohio State’s then-chair of educational services, Judy Genshaft, at a conference happy hour.

“I said, ‘I think I’d like to come to Ohio someday,’” Miranda recalls, even though she thought her husband, Jim — a dyed-in-the-wool New Yorker — would never go for it.

Genshaft said, “‘We’re going to have a position open. Are you interested?’”

Two months later, Miranda and her husband moved back to her hometown.

The transition was not easy. In 1988, academia was notoriously male dominated. Miranda struggled to balance a demanding teaching and research agenda and her growing family. But she leaned into her purpose, looking for those connection points to guide her. She found one in Head Start.

The bi-partisan initiative during Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty launched in 1965. The program meets the needs of the whole child — education, health and emotional development — before kindergarten. Miranda’s doctoral advisor at University of Cincinnati, David Barnett, had worked as a consultant for Head Start and set up practicums for his graduate students.

“I got early-childhood experience when most programs didn’t, because of him,” Miranda said.

At Ohio State, she saw an opening to implement Barnett’s approach. Federal law for teaching younger children with disabilities had expanded. Research program manager Donna Roxey suggested she write a preparation grant for training graduate students to work with children with developmental and learning disabilities.

Others discouraged her. “They said, ‘That’s a waste of your time. You should be trying to write articles,’” Miranda recalled.

She didn’t know how to write a grant proposal, so she borrowed successful proposals of colleagues and did her best to emulate them. She remembers the day Roxey called to ask if she was sitting down.

“It was a surreal moment, because everybody told me not to write it. And I did, and it got funded…,” she said. “Apparently, that year, they decided to fund more grants than they typically do.”

Following the nudges

Miranda used the Head Start grant to support graduate students like Laurice Joseph, ’97 PhD, who provided mental health services to young children and did home visits with families.

“She was able to fund quite a few of us on the grant, which helped cover tuition,” said Joseph, now a professor in the program. “Then, after the grant ran out … Head Start took over funding the students, because they thought it was so beneficial.”

That partnership continues.

Miranda has provided professional development to 19 Central Ohio school districts, training teachers in cultural competency, developing interventions and creating multi-tiered systems of support for children. She wove connections — this district to that graduate student, this alumna to that new graduate.

“Long after my tenure, (students) travel here to Florida,” Williams-Jones said. “And she’d say, ‘Hey, I’ve got someone working in (a Florida) district. Do you mind reaching out to them?’ Or ‘Someone’s in school down there. Do you mind sharing your experiences, helping them to understand that they have a place in the work that we do?’”

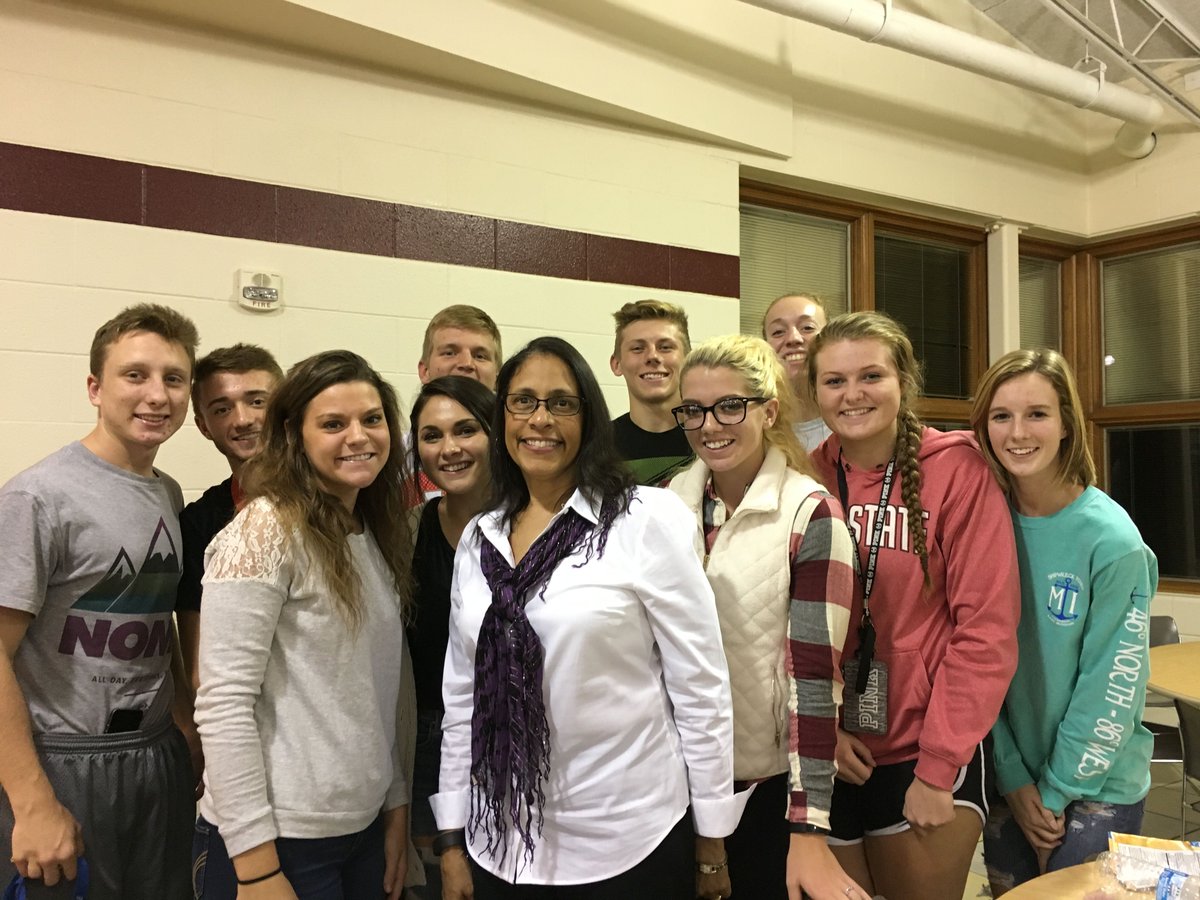

Miranda is known for letting her students crash in her hotel room at conferences and inviting them to high school games coached by her husband, an alum of the college. Desiree Vega, ’11 PhD, was 21 and knew nothing about Ohio when she took a Greyhound bus from New York to interview for the PhD program.

“Dr. Miranda really took me under her wing,” she said. “She very much integrated us into her family.”

“That has really stuck with me as a faculty member,” said Vega, now associate professor at University of Arizona, “the importance of building community, especially when we have folks who are coming from other countries, other states, without any family nearby. I feel it’s important to reciprocate that.”

When Vega got tenure in 2019, Miranda was there.

“Several of her students also have taken academia positions, and they’re doing really well,” Joseph said. “They’re receiving awards, and they’re becoming really known in our field.”

Miranda is a natural at connecting and supporting people, especially women of color, said Jina Yoon, now head of the Disability and Psychoeducational Studies program at the University of Arizona.

“I reached out to her and asked her if I could seek out some mentoring from her as I transitioned into administration,” Yoon said. “She has this air of supportive spirit and wisdom.”

Kelly Capatosto, ’14 MA, decided to steer away from school psychology while still getting her degree; Miranda didn’t miss a beat.

“She was simultaneously advising me in the program while getting my degree but also helping me chart a path for the next direction and thinking about how I can apply my skills,” Capatosto said. She graduated with a law degree from Harvard in 2024.

She admired how Miranda stressed public policy in class and later ran for and was elected to public office. Miranda also took on an administrative role in 2021, as chair of the college’s Department of Teaching and Learning.

“Her willingness to pivot and try new things while still maintaining her passion and her principles at the core — I think that’s the highest level of operation that we could all aspire to,” Capatosto said. “She’s one of my biggest sources of inspiration.”

If there is a gene for advocacy, Miranda has it, said Kisha Radliff, also an associate professor in the program.

“Her continual focus, to integrate in whatever she’s doing, is really in relation to cultural diversity. Whether that’s students of color, students who identify with the LGBTQ+ community, students who are first generation … she’s an advocate and supports and lifts those individuals up.”

Miranda’s influence is like a vine, wrapping its tendrils up and around as it grows. The intertwining of things — of people and opportunities for others. Not mere coincidence, these are carefully crafted moments in time, orchestrated by an advocate to many.

“She will be sorely missed,” Radliff said.

Antoinette Miranda: A highly celebrated career

- 2014 – First recipient of William H. and Laceryjette V. Casto Professorship in Interprofessional Education, Ohio State

- 2014 – Outstanding Trainer of the Year Award, Trainers of School Psychologists

- 2016 – Elected to the State Board of Education (District #6)

- 2021 – The Award for Outstanding Contributions to the Profession of School Psychology, the Council of Directors of School Psychology Programs

- 2021 – Chair, Department of Teaching and Learning

- 2023 – Legends Award, National Association of School Psychologists

- 2023 – Inaugural recipient of the Ann Brennan Outstanding Advocacy Award, Ohio School Psychology Association

- 2024 – President, Division 16, American Psychological Association

- 2025 – Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Humanitarian Award, Columbus Education Association