Last year, pandemic-era reading scores illuminated worrisome gaps in American children’s ability to read. But as news articles and radio reports pitted politicians against educators and sometimes parents against schools, researchers who study reading science were perplexed.

The terms politicians and reporters used were inaccurate, and their generalizations about approaches for teaching struggling readers were incomplete at best. Consider the much-touted “science of reading.” (Note the lowercase because no single “science” of reading exists.)

“I would argue that education scholars and the education community, writ large, should do a better job in defining what science of reading is,” said college researcher Shayne B. Piasta, “so it is not co-opted to mean something that is much more narrow than what that term actually refers to.”

The actual science of reading, to which Piasta has contributed more than 50 studies amounting to more than $47 million in funding, is a massive body of research spanning more than five decades. It includes thousands of studies — conducted in multiple languages — on the brain, phonics, reading comprehension, language, writing and Piasta’s seminal alphabet studies.

“The term has been used in ways where it’s referencing kind of a phonics-first, phonics-only approach, which is not accurate,” Piasta said. “Some people are calling for (getting) rid of the term because it’s been co-opted. I would argue we should do a better job of defining that and pushing back when it is being used to refer to something that is not exactly what we mean by the science of reading.”

What does science really say about learning to read?

The research makes it clear: While phonics is a critical part of teaching early reading skills, the science of reading never was about phonics alone.

“We know much more about additional skills that have to be supported as well,” Piasta said.

Piasta’s early work involved code-focused skills — foundational reading skills in which learners begin to recognize letter shapes and equate them with sounds. Her research determined that children should know at least 18 capital letters and 15 lowercase letters before kindergarten — a benchmark adopted by the federal Head Start Program.

“It’s not as easy of a task as we might think it is … Letters aren’t equally easy or difficult to learn. So, a letter like W tends to be really challenging for kids and might need more instruction than … the letter B,” she said.

This most basic skill, letter-sound correspondence, is just one that young readers must master. They also must become proficient in phonemic awareness, or recognizing letter sounds in spoken words. Think of these often-used classroom chants: “B-a-t, c-a-t, m-a-t.”

As children begin mastering these skills, phonics instruction helps children to read and spell. They work to become more fluent at reading words, both common “sight words” and those they have practiced sounding out.

“(These) code-focused skills are critically important,” Piasta said. “And I think we’ve gotten better and better at supporting those.”

But by themselves, Piasta said, code-focused skills are insufficient. And for some children taught using a phonics-only approach, that same “science of reading” evidence shows that some will later struggle to reach the ultimate goal — comprehending what they read.

For some children taught using a phonics-only approach, that same “science of reading” evidence shows that some will later struggle to reach the ultimate goal — comprehending what they read.

Reading crisis or chronic problem?

When national scores for reading proficiency declined in 2022, it wasn’t unexpected. Schools had been working for a year or more to overcome the impact of remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The average reading score for both fourth- and eighth-graders in 2022 fell 3 points compared to 2019, to 217 and 260, respectively, on a scale of 0 to 500. But what the headlines often didn’t report was that those scores had hardly changed in the last 30 years. In fact, the scores in 2022 are exactly what they were in 1992, with little variation in between.

“Is there a sudden reading crisis right now?” Piasta said. “I see it more (as) this has been chronic. And I think COVID just put more of a spotlight on it.”

The three-point dip is likely due to COVID. Piasta and many researchers remain confident that scores will return to pre-pandemic levels. In fact, some individual state achievement tests already show increases — even in urban districts like Cincinnati and Chicago — according to a report by Harvard and Stanford universities. More data is needed to be sure, Piasta said.

“But then the goal is to actually move beyond that and be better supporting these students,” she said, particularly for those most affected: children from backgrounds that for years have posed opportunity gaps in education. Poverty, race, disability and English-language learning create intersections where kids often fall through the cracks.

There has been and continues to be a divide among those who are learning.

The better path to reading improvement

Truly overcoming reading gaps means improving phonics instruction, yes, but also drilling deeper into what experts call meaning-focused skills, Piasta said.

A longitudinal study by Elizabeth Hadley, associate professor of literacy studies at University of South Florida, followed children from pre-K in 2020 through first grade in 2022. Hadley compared those children’s learning to that of other students who were the same age pre-pandemic.

“What we see here is that the phonics and foundational skills and the grammar and writing, there aren’t as big of differences,” Hadley said during a research forum by Ohio State’s Crane Center for Early Childhood Research and Policy. “We don’t have as large amounts of learning loss, especially for grammar and writing.”

That might be because remote learning can be adequate for teaching letter recognition, phonics and spelling — what Hadley calls constrained skills that are important but, once-learned, don’t need to be relearned.

But for comprehension skills, the study showed learning gaps became pronounced in first grade. “We’re starting to get above two points difference. And (for) vocabulary we’re seeing about four and a half points difference between the pre-COVID and COVID kids,” Hadley said.

In fact, by the end of first grade, the COVID-era students’ comprehension became even worse. And that points to the second type of skill that emergent readers must have and that phonics-only curricula might short-change — meaning-focused skills.

“Language and comprehension and conceptual knowledge are really, really key in order for us to understand … and make meaning from what we read,” Piasta said.

These meaning-focused skills — which also include vocabulary and being able to make inferences about things not explicitly stated in the text — are less understood and much more difficult to teach, she said. “It takes very talented and intentional teachers. It takes devoting time to that within the school day.”

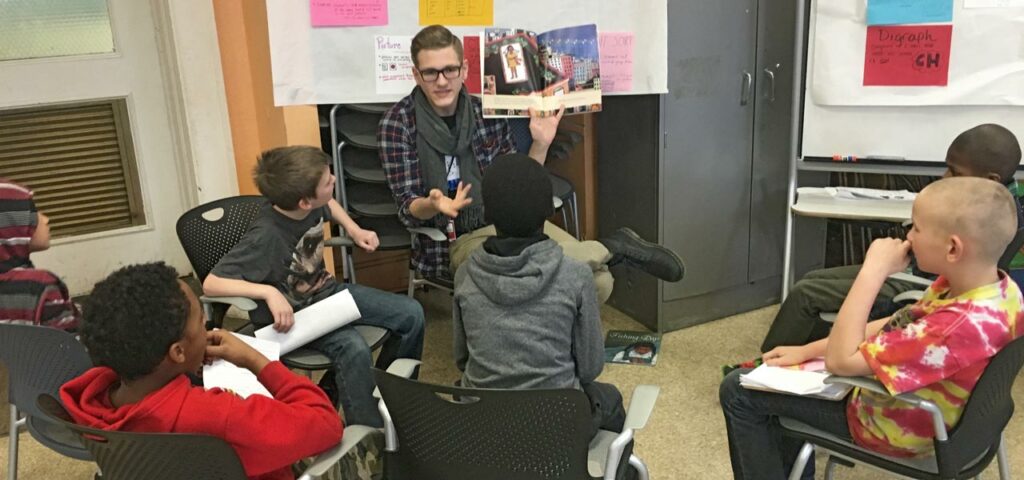

These skills have been a focal point of her work in recent years, especially supporting language development — the ability for children to express themselves orally and understand others within the classroom. Consider a teacher reading aloud to pre-K students.

“Are (the children) able to understand what they’re hearing as a precursor to being able to understand what they would actually be reading?” Piasta said. “This would include understanding language structures and vocabulary, and being able to tie words and phrases to background knowledge that they would have. If we’re talking about a farm, what does that conjure up for kids? Do they have a lot of knowledge about what farms are and what they look like and what might happen on a farm?”

Piasta and others are studying how best to bridge the gaps.

“What is happening within those classrooms that seems to lead certain children to have better language outcomes or more language learning than in other classrooms?” she said.

She was part of the multi-university Language and Reading Research Consortium that developed Let’s Know, a curriculum to build students’ language skills that the researchers tested in randomized trials.

Lessons on folklore and cause and effect allow kids to talk through what they are comprehending as teachers monitor them. A National Institutes of Health grant allowed Piasta and other researchers to expand the curriculum for small-group intervention. Findings will be available later next year.

What we continue to learn about reading

Disagreements over how to teach reading are as old as the Republic itself. In the 1700s, Benjamin Franklin created a “reformed” phonetic alphabet that he hoped would eliminate irregular spellings. In the 1840s, public education founder Horace Mann successfully campaigned to eliminate phonics-based instruction in American schools in favor of other methods.

Research not available in Mann’s day now includes brain scans administered as children read. It includes randomized control trials across numerous school districts and monitors student success across several grades. As Piasta’s research has done, it tries and retries interventions, looking at how teachers instruct, over how much time and with what success.

Since 2020 alone, more the 670,000 academic articles on reading have been published. This is the true “science of reading.” Distill much of that knowledge, and the debates begin to fade. Phonics and other code-focused skills are critically necessary, the science says.

But without meaning-focused comprehension skills, they are of little use.

“What we know from the science of reading is,” Piasta said, “it’s not an either/or. It’s a both/and.”

The science of reading: A definition

The accumulated, interdisciplinary knowledge from scientific research concerning the research process and its components, reading development and best practices for reading instruction and assessment.

Shayne B. Piasta