John Fuller is committed to setting an example. He was the first of his siblings to graduate high school, a first-generation college student, and he strives to be a role model for his seven nieces and nephews.

He has a distinct goal: to earn an advanced degree. “I’ve always known I wanted a PhD, even if the direction has evolved throughout the years,” he said.

Fuller’s passion for healthcare began when he attended Akron Early College High School. Upon graduating as valedictorian, he had earned enough credits to receive an associate degree from The University of Akron.

“Education was my escape from everything I was going through,” he said. “It empowered me, gave me a safe space and allowed me to be my authentic self.”

Professor James L. Moore III said he spotted Fuller as a future academic early, while recruiting him for Ohio State’s Young Scholars Program.

The college’s EHE Distinguished Professor of Urban Education made it his purpose to identify academically talented, first-generation, low-income students interested in pursuing higher education.

“I first met John, when he was in the tenth grade, through the Office of Diversity and Inclusion’s highly acclaimed Young Scholars Program,” said Moore, also a professor of counselor education and director of Ohio State’s Bell National Resource Center on the African American Male. “Soon to matriculate as an undergraduate student, John has soared in the classroom and as a campus student leader and student researcher.”

Riding the Young Scholars pipeline to Ohio State

When visiting campus the first time, Fuller immediately felt at home. “Everyone knew my name,” he said. “People are genuinely happy here. … I knew that something great was going to come from being a Buckeye.”

Fuller originally planned to major in nursing. But he suffered from the infamous imposter syndrome. “I was a Black male in a predominantly white, female field,” he said. “Less than 6% of nurses are males, and even less, Black.”

Several factors led Fuller to change his major to the Human Development and Family Science program. “The biggest reason is the community. I felt immediately accepted,” he said.

In addition, Fuller is earning a minor in Global Public Health and certifications in Health Communications and Diversity, Equity and Inclusion. “I’m really interested in health communication because I want to understand how providers communicate with their patients in ways that are meaningful, sustainable and culturally relevant for the communities they serve.”

Getting involved in research as an undergraduate

The first course Fuller took in the college was Life Span Development with Associate Professor Jen Wong. After class, Fuller approached her to say he was interested in getting involved in research. The next time class met, Wong handed him two pages of research opportunities. The college’s Virtual Laboratory School (VLS) caught his attention.

The Lab School, directed by Assistant Professor Sarah Lang, was developed to provide a virtual, research-based approach to professional development for child and youth educators on military bases worldwide. More recently, the free resource has been used by early education centers in the community.

“At the time, young Black boys were four times more likely to be expelled or suspended from preschool than their white counterparts,” Fuller said. “The statistic was worse for young Black girls; five times more likely.”

Fuller conducted qualitative research among local educators to improve the learning experience for these children. “I realized that research is about impact, that Dr. Lang’s research was impacting the entire Columbus community,” he said.

“John expressed an enduring commitment to creating more equitable educational opportunities, especially for Black children,” Lang said. On another project, “he worked with members of the VLS team to examine the inequities in early care and education experiences that may contribute to the lack of representation of people of color in STEM fields. He continues to bring a focus on doing what’s right for those most marginalized to all his research endeavors.”

Fuller was even first author of an article in an esteemed research journal about the importance of introducing preschoolers of color to science, technology, engineering and math.

Fuller also worked as a teaching assistant early in his undergraduate experience. At one point, “I was grading (the work of) about 250 students,” he said.

“As a TA, I used to send messages to my class about self-care. I remember a student told me I deserve endless love and rivers of chocolate.” Fuller was already making an impact on the lives he touched.

Fuller has collaborated with Autumn Bermea and Allen Mallory throughout his time at Ohio State. Both are assistant professors of Human Development and Family Science (HDFS) program.

“Dr. Mallory was my first Black instructor at Ohio State and later become a co-chair of my honors thesis committee,” Fuller said. “All of my knowledge about minority stress and theoretical frameworks came from Bermea’s and Mallory’s courses.” Now he’s applying those frameworks to his cancer studies.

Real-life stressor motivates interest in studying cancer

While Fuller was still a freshman, his father was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Fuller served as his parents’ medical guide, translating complex medical terms into practical language. He was experiencing first-hand the patient-provider communication he was so interested in studying.

“I really wanted to understand this disease that was taking my father away from me,” he said. “My father’s diagnosis was a catalyst to working in cancer research.”

At first, Fuller had doubts about his ability to do the work. “One of the biggest reasons is that I am not a bench scientist,” he said. The imposter syndrome again plagued his mind. “I was still in my early stages of becoming a researcher, and I had no cancer research experience.”

Despite the doubts, he persevered. He wanted to make an impact, to be radical.

Fuller applied for the CREATES (Cancer Research Experience for the Advancement and Training of Emerging Scientists) Undergraduate Program. The summer program pays Ohio State students to immerse themselves in cancer research under an expert.

He found a mentor in Elizabeth Arthur, a nursing scientist in the College of Nursing and an advanced oncology-certified nurse practitioner with The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center. “She was doing breast or chest cancer and that was my interest,” he said. Arthur’s work in cancer and nursing research also resonated with Fuller’s original interest in the nursing field.

“The CREATES program led to my independent study with Dr. Arthur,” he said. “We did about 44 interviews with survivors and their support people, and I remember thinking how courageous they were. We were asking a queer person to share their cancer diagnosis experience in a cis-hetero, patriarchal society.” During the first interview, Fuller came to fully appreciate the power of qualitative data to reveal personal narratives.

Applying to the Pelotonia Scholars program for undergraduates

Fuller’s study with Arthur took him to his next step. “The motivation that led to my Pelotonia (grant proposal) was almost all the interviewees were white, cisgender, lesbian, well-educated women. Many of them were saying, ‘I’ve never had a bad experience’ (during diagnosis and treatment). I knew this wasn’t true for my dad, so what about those who had adverse experiences?”

Arthur recognized Fuller’s strong commitment to the enhancement of cancer survivor experience for historically marginalized people. “John continually demonstrates a keen eye toward equity and inclusion, for example raising important questions about how Black and queer individuals are represented, studied and treated within clinical contexts,” she said.

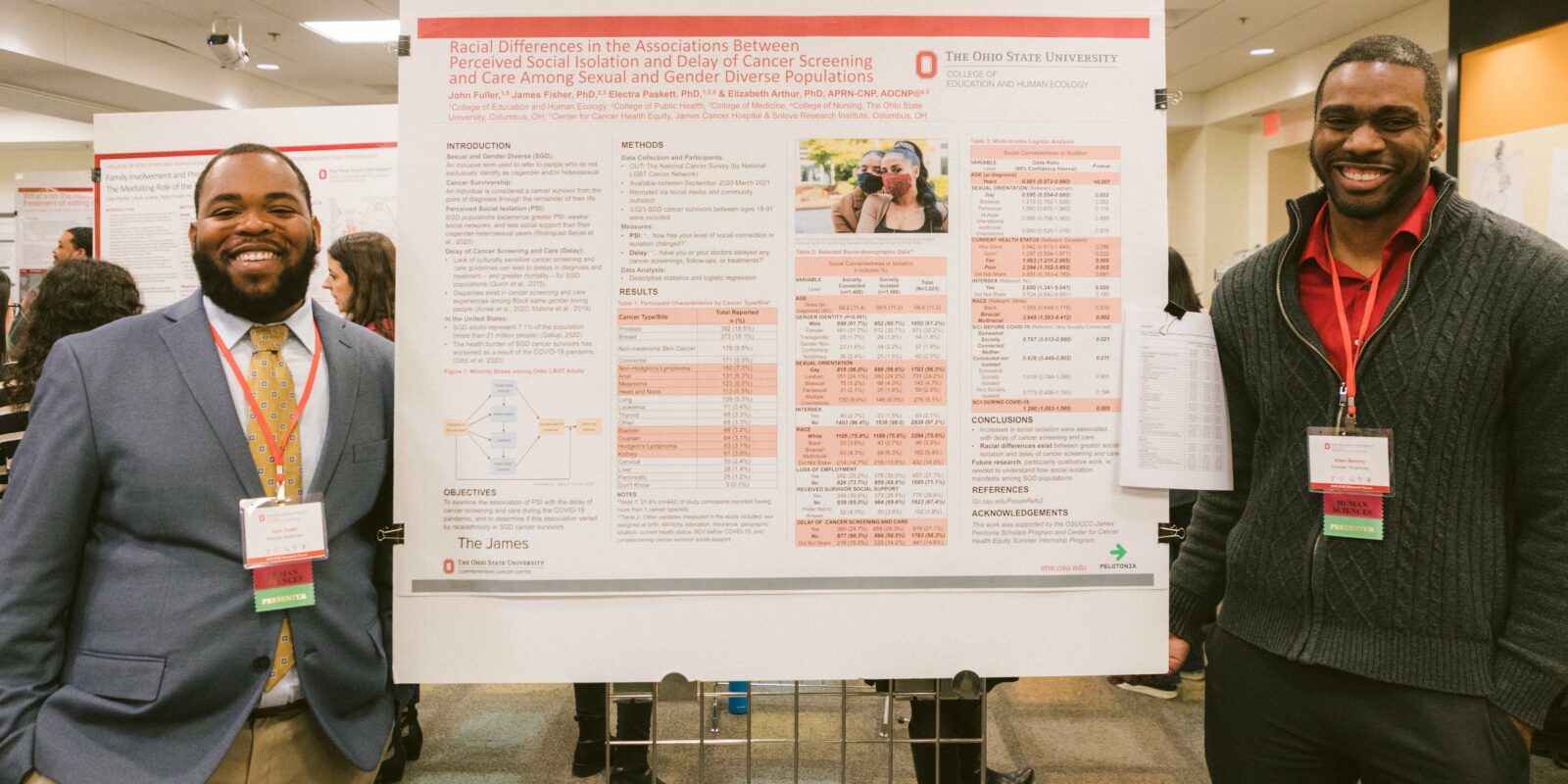

Fuller applied for a Pelotonia Scholars grant for undergraduates with a mission to explore the intersection of racial identity and sexual gender minority identity among cancer survivors. His Pelotonia grant also included a fellowship with the Ohio State Center for Cancer Health Equity.

“HDFS opened the opportunity for me to do social and behavioral research in cancer,” he said.

Fuller used secondary data from the OUT National Cancer Survey of LGBTQ+ Cancer Survivors. It is believed to be the largest sample of this population in the world.

He is focused on two studies. First, he is analyzing the association between perceived social isolation and delay of cancer screening, care and treatment among cancer survivors who are Black, Indigenous and people of color. The second study analyzes the association between social network support and frequent mental distress among the same population.

After working with the quantitative data from the OUT survey, Fuller wants to return to qualitative data for his PhD. “The reach of this work has potential to influence survivors, support persons, clinicians, policymakers and entire health care systems and cancer centers,” he said.

Fuller is the first Black, male undergraduate in the college to receive a Pelotonia Scholars grant. He is also the first undergraduate in the college to use his Pelotonia Scholars grant to conduct a population study, as opposed to scientific discovery conducted in a laboratory.

Fuller is being heavily recruited by esteemed PhD programs from across the country, including Ohio State, Harvard, Johns Hopkins, Emory and UNC Chapel Hill, to name only a few.

His advice to others: Be bold and don’t be afraid to take up space as a social scientist — challenge the status quo, he said. “Never say never. Wake up in the morning and tell yourself, ‘I might not know how it is going to get done, but it is going to get done.’”