For years, cringe-worthy films were a staple of American sex education: low-tech motion graphics demonstrated human reproductive systems while teenagers with outdated clothes and hairstyles awkwardly discussed sex. Students squirmed as health teachers projected anatomical diagrams of sexual organs onto classroom screens.

In the age of social media and video streaming, students these days might be less embarrassed. But they still are shown videos, online diagrams and book illustrations — visuals that are critical to teaching them about their bodies and reproductive behavior.

But those learning resources have never been accessible to students with visual impairments, who include those who are blind and partially blind. For them, sex ed curricula rarely take into account the unique ways they learn. But two Ohio State teaching and learning faculty are out to change that.

Students with visual impairments need comprehensive sex education as much as their sighted peers, if not more, said Tiffany Wild, associate professor of teaching and learning who specializes in sensory impairments.

“Students, if they don’t get this information, they’re going to go to other sources,” Wild said. “And some of those sources are not always accurate.”

Wild’s research shows that people who are visually impaired and don’t receive sex education tailored to their needs will look to the internet, pornographic videos and erotic novels to find answers.

“That is not the way that a healthy relationship works in the real world,” she said. “And, so, talking to them about sex education, talking through sex education, and what sex is and what a healthy relationship looks like, is very, very important. I don’t want them getting information from another source.”

Guiding new teachers to meet a critical need

Wild and her colleague, Clinical Assistant Professor Danene Fast, are among the minority of faculty who train preservice teachers to meet the learning needs of visually impaired students. They teach several Ohio State programs that address visual impairments, including a dual-licensure undergraduate program that is one of five in the nation working to fill the extreme shortage of teachers trained in the field.

The pair — who wryly introduce themselves as “Fast and Wild”— play off each other’s strengths and have the kind of fun-loving synergy that most coworkers wish for. But they are serious about creating access to learning for populations with visual impairments. Noted for their expertise in teaching how to make science accessible for students with vision loss, they train educators throughout the country.

“What’s sad to me is when an adult will come to one of these trainings — who is blind — and say, ‘Oh, my gosh, I didn’t know this. I didn’t know that’s what that anatomy really looks like,’” Wild said. “Or …. a parent who is getting ready to give birth has no idea about the birthing process — never taught about that. Scared. ‘What do I do?’”

Beyond not understanding their own bodies, lack of education puts some at particular risk: People with visual impairments experience sexual assault or abuse at rates of 11%-30% across the lifespan. But research is limited and more is needed, according to the National Institute of Health.

“Those are the stories that drive you to know that this work is so important … to get access to everybody,” Wild said. “It’s vitally important.”

Translating visual subjects for visually impaired audiences

Studies long ago showed that comprehensive, inclusive sex education reduces rates of sexual activity, risky sexual behaviors, teen pregnancy and STDs. Recent research shows that quality sex ed also reduces intimate partner violence, protects against sexual abuse and helps young people develop healthy relationships.

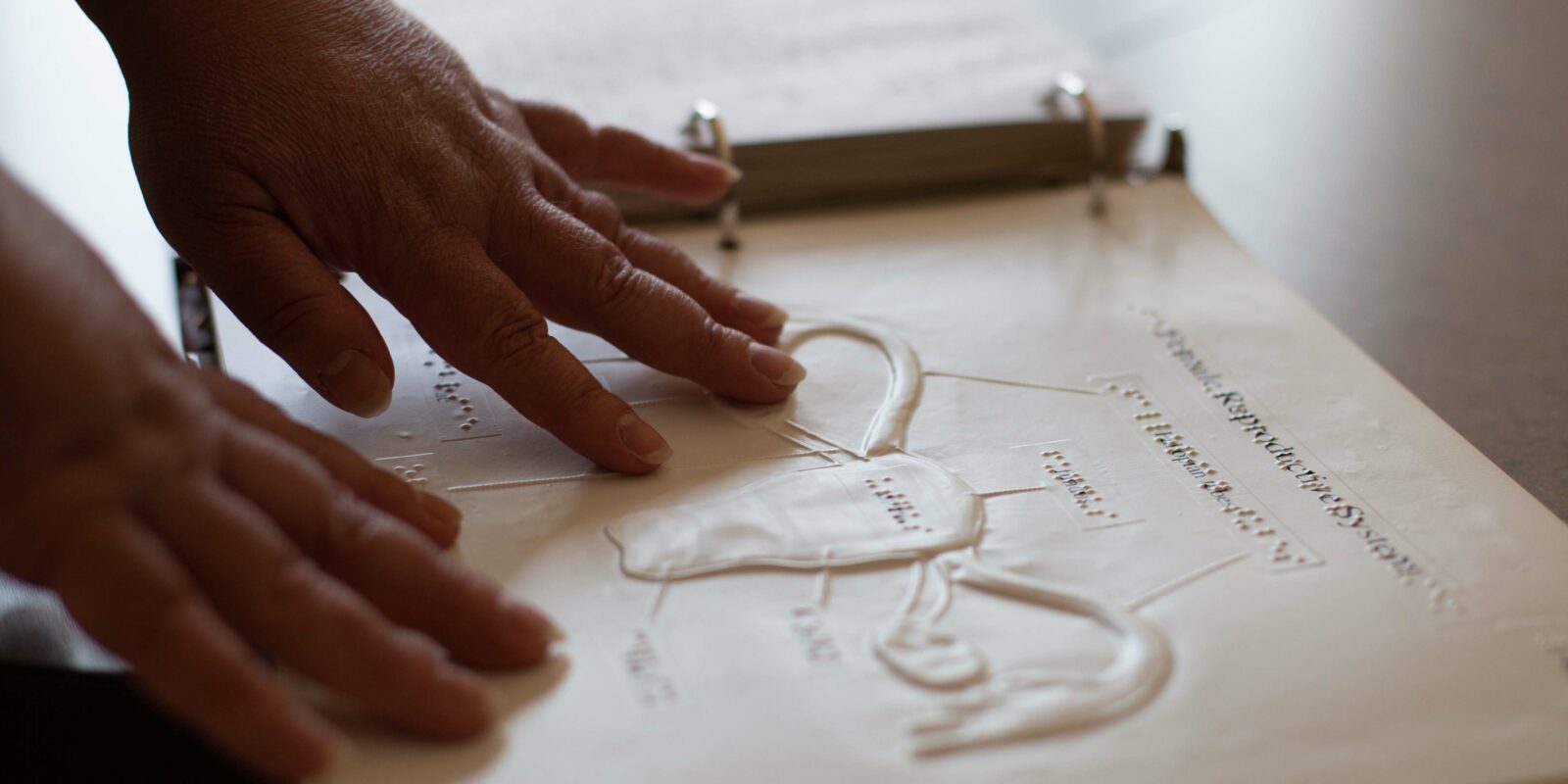

But for years, schools have relied on braille texts and tactile diagrams to convey these complex subjects to visually impaired students.

“Those are pictures that are basically raised up lines — you can feel them,” Wild said. “Well, when you put certain anatomy in front of a child — female anatomy — we will get things like, ‘Oh, this looks like a butterfly.’ ‘Oh, this looks like a moose.’”

Fallopian tubes, in fact, bear a striking resemblance to moose antlers in this format. And even when recognizing external anatomy, blind kids are at a distinct disadvantage, because they don’t see what others have since birth, Fast said.

“Students who are blind or visually impaired don’t have that same opportunity to see their parents, to see their peers, locker rooms, gym rooms … even when you’re babysitting and changing a baby’s diaper. A lot of times, those kinds of experiences just aren’t experiences that our kids have until they’re actually taught those experiences,” Wild said.

Traditional teaching methods often involve a “whole to part” learning strategy, in which students are presented a whole concept before learning the specific parts. A sighted child learning about elephants, for example, sees a photo or video and immediately understands the size, girth and mass of the creature. That doesn’t work for students with vision loss, Fast said.

“(For) a child who is blind or with severe visual impairment … we’ll talk about the rough texture of the skin,” Fast said. “We’re talking about the parts of the elephant. And they’re taking those parts and putting a picture together to create a whole picture.” Students with vision loss learn in a part-to-whole manner.

“One of the big things that I like to educate my (pre-service) teachers to do is use what we call a constructivist perspective in teaching, in that hands-on learning is just so important for our kids who are blind or visually impaired, and that conceptual development that comes with hands-on learning.”

Recognizing the need

In 2014, the American Printing House for the Blind — a nonprofit publisher and developer of products for people who are blind or have low vision — convened its annual “Meeting of the Minds.” Wild was among the educators and researchers who discussed needs of students who are visually impaired.

“It came up that we needed to have some sort of sex education/health curriculum for our students,” Wild said. “We never had it in our field. Our teachers were taking what they did in gen ed and trying to modify it.”

Two years later, the ‘minds’ revisited the topic and again identified inclusive sex ed as the greatest need for students with visual impairments.

“A colleague of mine from across the room says, ‘Wild, you do science. … Isn’t health and sex just biology? … You need to lead this team.’”

Considering the dearth of research on sex education for students who are blind, the thought of creating a first-ever teacher guide on the subject was intimidating.

“We didn’t know what to do,” she said. “But when I thought about my core value, access to education … I’m a big proponent of making sure that every child can learn whatever the content. I say this over and over again. And I thought, well, if I say it, I’ve got to do this.”

Writing the first guide

Wild researched and oversaw the writing by a team of experts for a teacher guidebook, Health Education for Students with Visual Impairments, published in 2020. It includes sections on diet and nutrition (cowritten by Ohio State nutrition researcher Sanja Ilic), disease prevention and safety. The chapter on sex education was co-written by a blind special education professor, Gaylen Kapperman and his colleague Stacy Kelly. The book is also available in braille.

Wild felt it was imperative that a classroom teacher work alongside researchers, so she enlisted Alison Brewer-Wood, who has taught both health and sex education to students with visual impairments.

Sex ed curricula vary dramatically. Within Ohio, for example, contiguous districts can teach it in very different ways or not teach it at all. The book guides teachers with tools and lesson plans specifically geared to visually impaired people — emphasizing areas that go above and beyond what a general education teacher typically teaches.

To make learning tactile, the guide points to resources such as medical anatomical models or instructs teachers how to make their own using sponges, vinyl tubing and foam pipe insulation. Unlike hard plastic models, the materials mimic the feel of skin. The handmade models are less realistic than they are concrete representations of abstract concepts: tubes with small beads in them demonstrate ovulation; a squirt bottle can illustrate conception.

“We give you the recipes for those bodily fluids in the book, and we can push those through the tubes,” Wild said. “So the students understand where things come out, why the mechanics of your body work the way that it works.”

Back to the elephant example, these lessons can be applied in a part-to-whole fashion, Fast said, helping kids with visual impairments learn better.

“We can take those parts of the models, and we can have them actually assemble them in a lesson to actually understand, okay, these parts come together” to create an anatomical system within the body, she said.

Because more than 80% of students with visual impairments are taught in general education schools instead of specialized schools for the blind, most learn next to students who can see. That’s why Ohio State’s visual impairment programs are so vital for training their teachers. But the hands-on nature of activities for blind students provides solid lessons for sighted students as well, Fast said.

“We always tell our gen ed teachers, if this works for students who are blind or visually impaired, it actually works for all students,” she said.

Navigating puberty when you cannot see your peers

Still, students with vision loss aren’t always on the same page as their sighted peers. Sex ed is also human ed; navigating life stages, like puberty and dating, pose special challenges. Adults in Wild’s studies say that, as teenagers, they needed to know more than the mechanics of sex. Wild and Fast teach teachers to be attuned.

“As other kids are maturing, sometimes our (visually impaired) kids aren’t maturing at the same rate, because they’re not seeing the changes that are happening in their peers,” Fast said.

Wild tells teaching students about a teenage boy, rapidly losing his vision, who wanted to ask a classmate to a dance.

“His big concern was, ‘I’m so used to seeing facial reactions, and now I can’t see this,’” she said. “So, what if she says yes, but really, she’s making some sort of face, like, ‘Oh, I don’t want to do this.’”

Together they came up with a plan for Wild, then a teacher, to hide behind a locker, watching the girl’s reaction from a distance so that she could reassure the student.

“That illustrates the importance of really talking through social skills, and proximity to … how close you’re going to be when you talk to somebody, if you can’t see how close they are? How do I figure that out? Things like those facial reactions, (is she) really saying yes? Or (is she) really saying no, because I can’t see your face? And what you can listen to in the voice?”

Sex education, particularly in the current political climate, is controversial. It’s an uncomfortable subject to teach. So, Wild and Fast instruct their teaching students to seek parental permissions, know district policy and consider cultural taboos and limitations, such as age appropriateness.

Their work is so vital that they consistently are asked to present it around the country. In 2020, Wild received the Warren Bledsoe national award from the Association for the Education and Rehabilitation of the Blind and Visually Impaired for the guidebook. And while Wild is quick to credit her team of authors, teachers search for her name on the internet.

“They have called me randomly and just said, ‘Thank you for doing this,’” she said.