Listen to Inspire Podcast

Sports have for decades been a platform for social activism. Today, athletes from the WNBA to college campuses are speaking out more than ever against the injustice they and others face.

Because civil rights come in many shapes and forms, it takes a diverse army of champions to defend them. Martin Luther King, Jr. understood the power of sports to advocate for human freedoms. He would no doubt applaud the work of one Ohio State University Muslim student who, at 16, stood tall for civil liberty.

In 2019, Noor Alexandria Abukaram had just completed a 5K with her high school cross-country team in Toledo, Ohio, running a personal record of 22 minutes, 22 seconds. She was feeling confident until she realized she wasn’t listed among the finishers.

“When my teammates told me that I was disqualified, I asked, ‘For what?’” she said. “That split second before they answered, I thought it was for my bracelet because I always wear a bracelet.”

“They’re like, ‘No, no. It’s not your bracelet. It’s because of your hijab.’”

Humiliation doesn’t begin to describe what Abukaram felt. As the only Muslim runner on the team, she already had struggled with feeling like an outsider.

“I didn’t want to be there,” she recalls. “I didn’t want to ride the bus home.” Her mother picked her up at the meet. Though her coach had forgotten to submit a waiver exempting her from a rule banning head coverings, the rule felt discriminatory — even to a teenage kid. Abukaram’s hijab is part of who she is, and it had been summarily rejected.

“I was 16 years old. And it’s crazy to think back to who I was three years ago and who I am today.”

Who she is today is an unapologetic, tenacious advocate for Muslim women athletes everywhere. Now an Ohio State freshman majoring in fashion and retail studies, Abukaram plans to expand her major into sport industry as well.

Back in 2020 she linked arms with advocates, including her mom and a state senator, to fight the Ohio High School Athletic Association rule that disqualified her. She founded Let Noor Run, an advocacy group for Muslim women athletes, and spoke to groups around the country.

“My older sister said … ‘Noor, we have a younger sister, who’s going to want to wear a hijab one day. And she’s going to want to play sports one day. And it’s our duty, and it’s what we’re supposed to do for her: Pave the way for her so that she has no roadblocks in the way that we have had to face.’”

In February, Abukarum’s activism paid big dividends. The Ohio bill protecting high school athletes’ religious expression while playing sports passed unanimously. Two other states soon passed similar laws.

Sports have long been a forum for civil rights activism, said the college’s Associate Professor Kwame Agyemang, who studies activism surrounding race, justice and equity in the sport industry, and how Black sports professionals in particular respond to injustice.

“There’s a lot of talk about how sports and politics should be separated, and how there’s no room in sports for politics. But that’s farthest from the truth…” he said. “Sports and politics have a long history of being linked.”

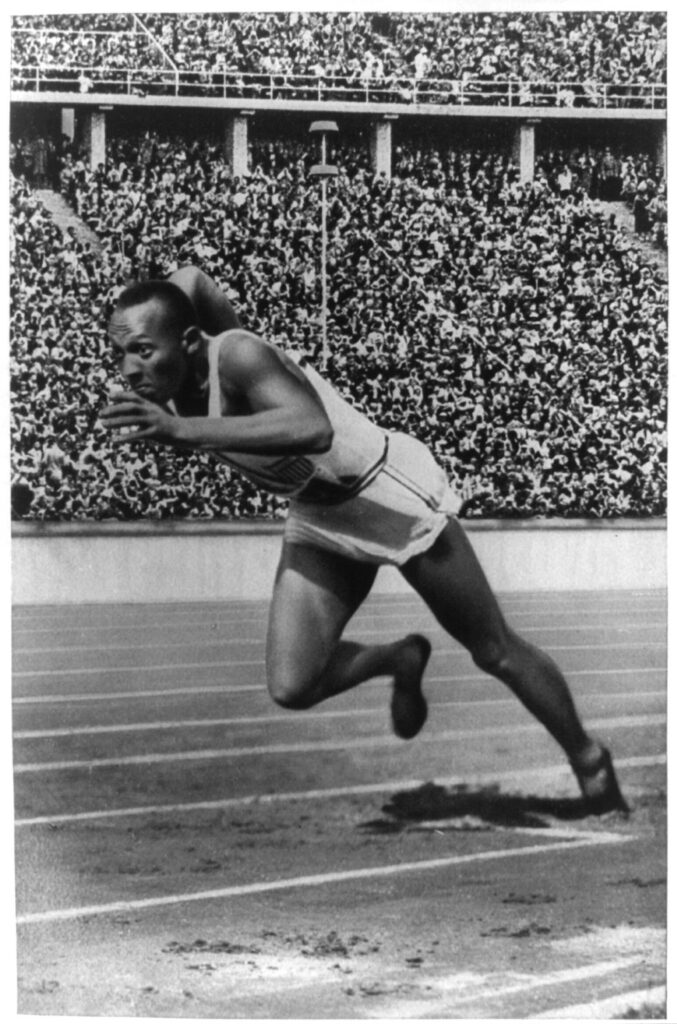

Hitler, for example, used the Olympics as a propaganda tool for white supremacy. Ohio State’s Jesse Owens famously refuted those claims through his dominant performances in the 1936 Olympic Games. When Morocco took on its former colonizer, France, in the Men’s World Cup in December, political histories were rehashed.

“We see politics and sports — the nationalism — that takes place. The singing of the national anthem, flying jets over the stadium,” Agyemang said. “Politics are always playing out in sports, and it offers a large platform for activists to convey a message to a large amount of people.”

Agyemang and several sports industry figures, including former Ohio State and NFL football player Malcolm Jenkins, discussed the role of sports in advancing civil rights in January at the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Commemorative Event, hosted by the College of Education and Human Ecology.

Scholars like Agyemang point to the work of Harry Edwards, who was a part-time college lecturer when he called on Black athletes to boycott the 1968 Olympics. Edwards would later define the movement with his scholarship, describing periods of sports activism as “waves.”

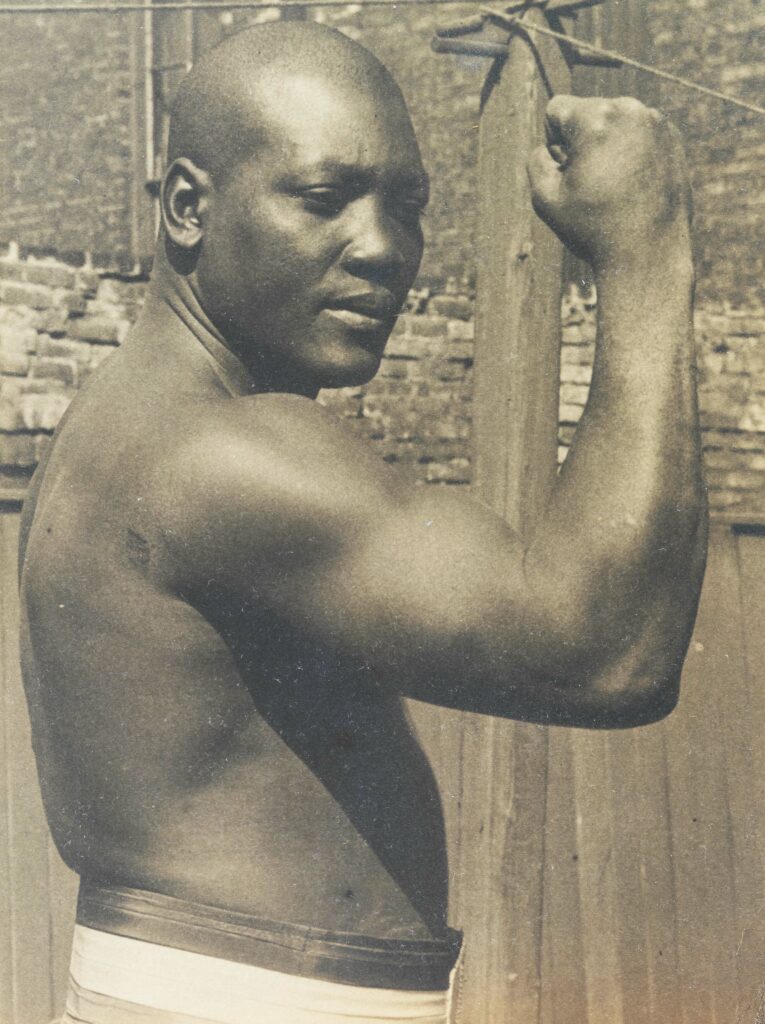

Wave One saw pioneering Black athletes, including Owens and boxers Joe Lewis and Jack Johnson, fighting for recognition and legitimacy in an openly racist society. Wave Two was about athletes such as tennis champion Althea Gibson, breaking the color barrier. But the third wave saw athletes use sports in ways they hadn’t before, as a platform to call for significant societal change, Agyemang said.

“This was largely fueled by the Civil Rights Movement at the time,” in the mid-1960s and ’70s, he said.

Edwards’ work planted a seed in John N. Singer, ’02 PhD, to study the intersection of race, sports and education. Now an associate professor at Texas A&M, Singer wrote a book on the topic in 2019.

“You had the third wave of activism, this focus on power and respect,” Singer said, “where these Black athletes were demanding (respect) from the white establishment and the sport industry: You’re going to give us our respect. And we’re going to take our respect, and we’ll show you how, by not playing, by boycotting, by engaging in some of the similar tactics and strategies that the broader Black power movement and Civil Rights Movement was engaged in at the time.”

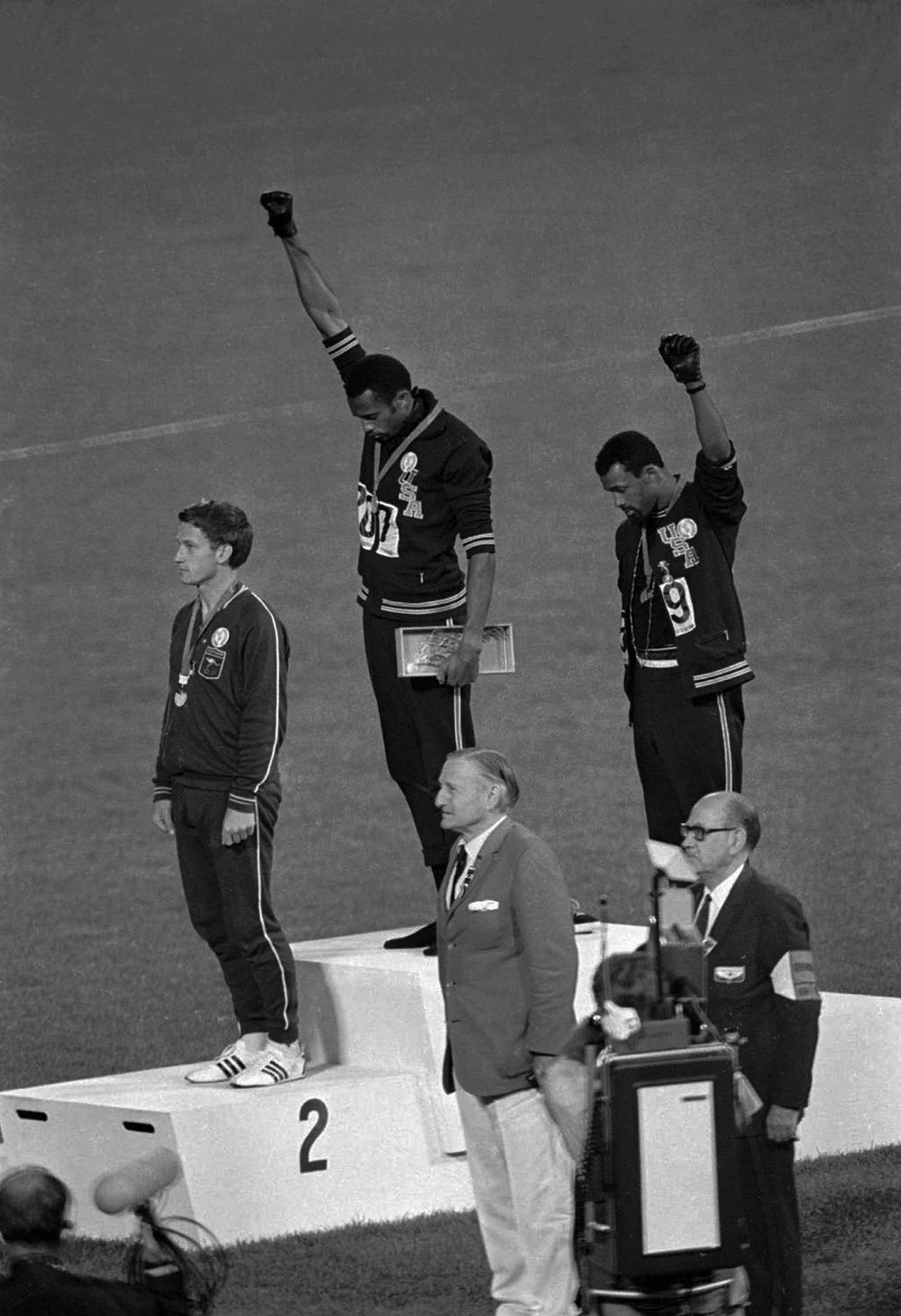

Activism within sports met with heavy resistance in the ’60s and ’70s. When runners Tommie Smith and John Carlos famously raised gloved fists on the medal podium at the 1968 Olympics, they were protesting racism and the poverty of Black Americans.

Weeks before his assassination that year, King met several athletes. “Dr. King was in my mind and heart when I raised my fist on that podium,” Carlos later told sportswriter and filmmaker Dave Zirin.

Smith and Carlos were booed by the crowd and then summarily dismissed from the games by the U.S. Olympic Committee. They later said officials tried to confiscate their medals, but they refused to hand them over.

Extending gloved hands skyward in racial protest, U.S. athletes Tommie Smith, center, and John Carlos stare downward during the playing of the Star Spangled Banner after Smith received the gold and Carlos the bronze for the 200 meter run at the Summer Olympic Games in Mexico City on Oct. 16, 1968. Australian silver medalist Peter Norman is at left. (AP Photo)

Sports activism stagnated for nearly 40 years beginning in the late ’70s. Many say this was fueled by shoe sales and soft drink ads.

“Craig Hodges (of the Chicago Bulls), who was very much an activist, wanted Michael Jordan to protest (the Gulf War) in 1992 when they went to the White House, after they won their second championship,” Agyemang said. Jordan refused.

“With Michael Jordan being the most highly sought-after brand for corporations and his influence on sports and society and culture, many felt as if he could have done more to speak on issues of that time,” he said.

Jordan was infamously quoted as saying, “Republicans buy sneakers, too,” when asked why he didn’t weigh in on the issues. He later said he was joking.

“Many of the gains that were gotten (during the Civil Rights Movement) were reversed, particularly in the ’80s,” Singer said.

That changed with the advent of social media. The 2008 election brought the first Black American president and the following years ushered in Facebook, Twitter and the beginnings of the Black Lives Matter Movement.

“Black athletes had a platform,” Singer said. “They didn’t rely just solely on the mainstream media anymore to define self and the social causes they wanted to throw their platform and weight behind. That coming together of all these different … societal (changes) really contributed to the fourth wave of athlete activism.”

When LeBron James tweeted a photo of the Miami Heat wearing hoodies in 2012, the team was protesting the slaying of teenager Trayvon Martin. In 2014, James and his Cleveland Cavs teammates wore “I Can’t Breathe” t-shirts, protesting Eric Garner’s suffocation death in the presence of police.

In 2016, when ’49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick was reviled by politicians for taking a knee during the national anthem, his Twitter feed was filled with messages about civil rights. After that, Megan Rapinoe took a knee on the soccer field, too, and others followed their lead.

The pushback was not unexpected. Journalist Laura Ingraham gnarled in 2018 that James should “shut up and dribble.”

But, by then, athletes controlled messaging that connected them directly to fans, and their activism gathered momentum. After George Floyd was murdered by a Minneapolis police officer, and then Jacob Blake was shot by police months later, the Milwaukee Bucks players boycotted their playoff game. The NBA cancelled all three games in response.

During the 2020 U.S. Open, tennis player Naomi Osaka each day wore masks with different names of victims of racial violence.

Even college athletes, including The Ohio State University football team, crafted social media messages supporting Black civil rights. It didn’t make sense for college athletes to stay silent in that moment, said Joy Gaston Gayles, ’02 PhD, a professor who studies racial inequity in college athletics.

“Everything that happens in society impacts all microcosms of society … including intercollegiate athletics,” she said. “And so, many of us who hold marginalized identities, we don’t have a choice to disassociate one thing from another. So, something like George Floyd being murdered has implications for me, in all aspects of my life. If I’m a student athlete, it carries over to that space.”

Will history look at these activist athletes differently than their detractors have? If Martin Luther King Jr.’s legacy has taught us anything, Agyemang said, the answer is yes.

“The FBI and many white people, they despised him. But you fast forward 40 or 50 years, he has a national holiday,” he said.

People laud King’s form of peaceful protests. But that’s playing revisionist history, Agyemang said.

“Because, during his last years, MLK was a lot more forthright in his speeches, in his writings, talking about the dangers of the white moderate. … We don’t really talk about those stories,” he said.

“So, I think, in time, the same could hold true for people like Colin Kaepernick.”

Timeline of Activism in Athletics

Reno, Nevada

1910

Jack Johnson

Becomes first Black world heavy-weight champion, triggering protests across the United States.

Rutgers University

1918-1919

Paul Robeson

Earns All-American on the Rutgers football team even after teammates broke his shoulder and nose during aggressive tryouts.

Berlin Olympic games

1936

Jesse Owens

Proves Hitler wrong by becoming the most successful athlete in the 1936 Olympic Games.

Brooklyn

1947

Jackie Robinson

Becomes the first Black player in Major League Baseball.

Paris

1956

Althea Gibson

Is one of the first Black athletes to cross the “color line” in international tennis. She was the first African-American to win a Grand Slam title.

Houston

1967

Muhammad Ali

Protests the Vietnam War by refusing to be drafted.

Mexico City Olympic Games

1968

Tommie Smith and John Carlos

Earn medals in the 200-meter dash and then, on the medal platform, protest racism in America.

Worldwide

1970-1980s

Dead period

Commercialism of sports dampens social protest in athletic spaces.

Chicago

1990

Michael Jordan

Infamously says “Republicans buy sneakers, too” when asked why he didn’t engage in political discourse.

Washington D.C.

1992

Craig Hodges

Is let go from the Chicago Bulls after protesting the Bush administration for its treatment of marginalized people.

Miami

2012

Lebron James

Tweets a photo of the Miami Heat wearing hoodies in support of Trayvon Martin.

Washington d.c.

2014

Georgetown Basketball Team

Wears “I can’t breathe” t-shirts in support of Eric Garner.

St. Louis

2014

St. Louis Rams

Come on to the field with their hands up in protest of Michael Brown shooting.

San Francisco

2016

Colin Kaeperinck

Takes a knee at a San Francisco ’49ers game.

Across United States

2022

WNBA

Professional women basketball players take a stand against Brittney Griner’s and others’ imprisonment overseas.

Columbus, Ohio

2022

Noor Alexandria Abukaram

Fights against discrimination of Muslim athletes, winning the right in Ohio for women to wear hijabs while competing in sports.