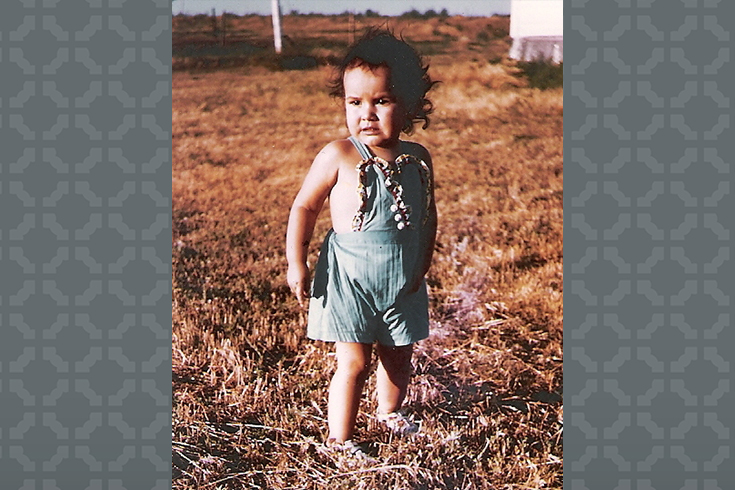

On the day they came to take her, Sandy White Hawk experienced her first disassociation. She was just a toddler, so she didn’t know what that was.

She only knew that she suddenly was standing in the bed of a pickup truck “looking through the window at this little brown girl, how scared she was and how she was crying,” White Hawk recalls.

The girl was in fact her, a Sicangu Lakota child sitting between her new adoptive parents, who were both white.

“So, I left my body at 18 months old,” she said.

Disassociation, psychologists say, can occur when people experience extreme trauma. The episodes continued long after White Hawk was removed from South Dakota’s Rosebud Reservation, because the trauma continued for years.

“I remember hiding from her, being under this kitchen table and hiding,” she said of her adoptive mother. “She had polio. So, her one leg was sort of crippled. And, so, she didn’t get down on her hands and knees and come get me out from under the table.”

“She used to always say, ‘You were a nervous wreck when we got you. You needed to be away from the reservation,’” White Hawk recalled. “I was not a nervous wreck. I was terrified because these were strangers. I didn’t know who these people were. Plus, I started getting violated right away. She always put that on me. So as a child, as a young adult, that became…my identity. There’s something wrong with me.”

Years later, after swearing off the alcohol she had used to deaden the trauma, she pieced together fragments of memories. She emerged from a dark tunnel of addiction and self-doubt, and eventually made her way back to the Rosebud Reservation. There, she found not only a brother, sisters, aunts and uncles, but also a calling.

She would discover that she was not alone. Tens of thousands of Native children, not just from South Dakota, had been adopted and fostered by non-Native families. They were removed from reservations and placed in boarding schools, cut off from their heritage and from people who looked like them. And a disproportionate number of them were abused, just like her.

White Hawk was determined to do something about it. It would take a community, including a researcher from The Ohio State University, to help her.

Tribal sovereignty affirmed, but now at risk

Had she been born 25 years later, a law introduced by a U.S. senator from White Hawk’s birth state could have changed everything for her. The Indian Child Welfare Act was enacted in 1978 to stop the systematic removal of American Indian children from tribes.

Before then, 25% to 35% of all Native children in the United States had been separated from their families and placed in foster care, adoptive homes or institutions. Ninety percent of those were placed in non-Native homes, outside of their culture. The American child welfare system was intentionally decimating Native tribes.

The 1978 law gives sovereign tribal governments a voice about where their own children go: They must first be placed with extended family and, if not, then with tribal members. If no Native home can be found, then the child may be placed in a non-Indian home.

William Thorne served as a tribal judge and state court judge for a total of 34 years, presiding over numerous custody cases for both Native and non-Native families. He now works to educate lawyers and judges on the realities of foster care and adoption.

“I’ve seen the downside in the state system — the Anglo system of doing it,” Thorne said. “Because by the time I have left the state court, I’ve seen second-, third-, fourth-generation kids in foster care.”

“We didn’t do a very good job with their great grandparents,” he said. “We didn’t do any better with their grandparents (or) their parents. What makes us think it’s going to be any better today? That’s the layman’s definition of insanity. If we want a different result, we need to consider doing things differently.”

When properly administered, the Indian Child Welfare Act is the gold standard, says the Casey Family Foundation.

“Think of it as the pilot program for what child welfare ought to be for everybody,” Thorne said, “Active efforts, connection with community and higher standards of proof before we remove kids. All those kinds of things ought to be available to every family that goes into the system, not just Indian families.”

The Indian Child Welfare Act, or ICWA, prioritizes the need for family and cultural connection, not “owning” rights to the child, Thorne said. Kids might have eight grandparents and a host of aunts and uncles, adoptive but also birth relatives, guiding and affirming them.

“It’s about respecting the child’s right to call on this wide range of people for any help they need. You get past the point where the Anglo system pretends these kids were found in the cabbage patch, would erase all of their relatives and say we’re going to start over. That’s unrealistic, and it’s a disservice to the children.”

But the law is not without its detractors. Since enacted, numerous challenges, including the notorious Baby Veronica case, have questioned the constitutionality of ICWA. On Nov. 9, the U.S. Supreme Court will hear arguments to overturn the law, which could have consequences far greater than just deciding with whom Native children belong.

Research shows disproportionate harm

White Hawk met Judge Thorne roughly 20 years ago in the basement of a casino in Pine Ridge, South Dakota. He was teaching a class about Indian Child Welfare when she told her story and spoke about how failure to comply with ICWA affects Native kids.

“We started talking about what her hope was … brainstorming what pieces needed to fall in place,” he said. “She was just beginning to have this thought about creating the First Nations Repatriation Institute.”

Another tribal judge had impressed upon White Hawk that the history of Native adoptees must be told, that the retelling would bring healing for them. White Hawk founded the institute to help reunify adoptees with each other and their tribes, but also to illuminate what happens when Native children are severed from their heritage.

“We don’t laugh like anyone,” she said. “We don’t have toes like the rest of the cousins. We don’t have anything that connects us genetically. There is absolutely zero genetic juice. We feel the lack of that when we watch bio relatives interact, even if they love us. The absence of that is impactful.”

She served as an expert witness in Native adoption cases that were becoming more prevalent as states found workarounds to the Indian Child Welfare Act. But lawyers representing adoptive parents were calling hers an isolated case.

“At the time, there were only five research papers done on Native American adoptees,” White Hawk said, “and the largest number of adoptees interviewed was 20. And in those papers, there still wasn’t conclusive information” about risks of Native adoption.

“And I left this one situation just so mad, and I just thought, somehow we’ve got to get some research going.”

Through a contact at University of Minnesota, she met Ashley Landers, then a doctoral student studying complex trauma and family reunification. Now an Ohio State University assistant professor of human development and family science, Landers and White Hawk together have researched the impact of foster care and adoption on Native people. The results, some presented in an amicus brief in the SCOTUS case, are shocking, though no surprise to White Hawk.

“What we ended up finding is that a lot of Native fostered and adopted individuals actually experienced re-victimization in their foster and adoptive homes at high rates, and that they were more likely to experience victimization,” Landers said.

The Native participants, in fact, were significantly more likely to report physical abuse — 64% compared to 38% of white respondents — and sexual abuse — 32% compared to 21% of white respondents. Nearly half of the Native individuals studied experienced spiritual abuse: racial slurs or rejection of their spiritual practices.

“And it wasn’t just emotional or physical or sexual or spiritual abuse,” Landers said. “It’s oftentimes what we would refer to as poly-victimization, or complex trauma. It’s these cumulative experiences of victimization.”

Opponents of ICWA, even a few liberal ones, argue that some Native children have died after being returned to biological parents. That’s a failure of the child welfare system in general, Landers said.

“It is always a tragedy when a child dies, but non-Native children are returned to non-Native parents and die, too. That is usually omitted from the story,” Landers said. “So, it’s not that the Indian Child Welfare Act is harming Native children. That’s really a misconstrued idea.”

“Our research says that Native fostered and adopted individuals suffer from grief and loss; they are disconnected from their culture; they don’t know who they are; they have mental health problems; they have higher rates of suicidal ideation. We know that reconnecting to culture is helpful,” she said.

But, still, Native children are placed in foster care at twice the rate of their peers, studies show.

“It is the systematic removal of Indian children and the implicit bias of the child welfare system that targeted Native families that makes this issue so pressing….” she said. “We don’t believe that the rates of maltreatment (within Native families) differ but that the issue is the child welfare system, systematic bias and misunderstanding of Native families that constitutes their removal.”

What’s really at risk?

The case before SCOTUS, Haaland V. Brackeen, was filed by Texas and several plaintiffs. Those include a Minnesota couple who tried to adopt a six-year-old whose grandmother is from the Ojibwe Tribe. Those plaintiffs’ claim asserts that this child and others ultimately were placed with Native families based on their race.

That argument is false, said Shannon Smith, director of the ICWA Law Center that successfully helped argue the initial Minnesota case in state court. The Texas judge never considered facts that Minnesota heard before placing the child with her grandmother.

“There was no testimony. There wasn’t any kind of fact-finding. It was like a summary judgment motion, where it’s basically attorneys submitting briefs,” Smith said. “So, it’s a procedural mess. But where witnesses provided testimony, the Minnesota Court found that it was in this child’s best interest to be with grandma.”

This decision was grounded in state law, and not on ICWA alone, Smith said. But even if ICWA was the basis, race wouldn’t have been a factor. ICWA is about tribal sovereignty, Smith said, not race.

“It is this long history with the legal precedent going back to the Marshall Trilogy,” she said, when the U.S. Supreme Court recognized tribes’ unique relationship with the federal government. The resulting dual sovereign structure still governs today.

“Tribal nations have inherent sovereignty that the federal government has acknowledged and has also, through treaties, indicated their responsibility to protect and honor,” she said.

Overturning ICWA threatens not only a 44-year precedent that has kept tribal families together, but the sovereignty of tribal nations at all, said Thorne.

“The racial versus political construct for tribal membership was one of the issues that (the Court) said they wanted to hear argument on,” Thorne said, “which means they’re willing to reconsider that question, and possibly overturn 200 years of case law.”

That threatens the ownership of Native resources such as mineral and water rights, the existence of reservations, even the rights of tribes to be governments at all, he said. It could effectively abolish tribes.

“We sometimes forget the fact that there was outcry,” Landers said, “that there was outrage within these (Native) communities. That they rallied together to say (Indian child removal) wasn’t acceptable. And the challenges to ICWA now are really undermining tribal sovereignty to define themselves.”