As society evolves, early childhood education should, too. Why the preschool of 1995 (or even 2010) doesn’t cut it anymore.

When PhD candidate Colin Page McGinnis attended preschool in 1997, the goal was purely to help him socialize. His mother had not yet returned to work, so if he didn’t want to go on a particular day, he stayed home.

“For others in my class, though, if they didn’t go, their family couldn’t work,” said Page McGinnis, who studies human development and family science.

There was an underlying class component to who went — particularly in the younger years — who participated in early childhood education, who didn’t need childcare and who was going to preschool. How the families would talk about it and the vernacular they would use would really tell you which side of the fence they fall on.”

In 2021, those distinctions have blurred. Low-income families remain gravely impacted by lack of childcare. But a job-shifting pandemic made crystal clear that the burden of finding quality care for children falls on parents in many job sectors, not just essential workers.

A Department of Treasury report in September deemed the country’s current childcare system — with its high costs for working parents and rock-bottom salaries for workers — “unworkable” and a “classic market failure.”

At the same time, a plethora of research underscores the critical impact that quality, well-resourced early childhood education can have on learning and other milestones, through kindergarten and over a lifetime. Ohio State’s Crane Center for Early Childhood Research and Policy is at the forefront of that research.

Now a renewed push for universal pre-K by the Biden administration has policymakers arguing the merits of full access to not just childcare but early childhood education — a system whose structure hasn’t innovated in a comprehensive way since the Head Start Act of 1965 opened access to the lowest-income children.

Quality early education is expensive

Business leaders today recognize that current shortages of workers — from nurses to teachers to factory workers — is at least in part due to the critical need for affordable childcare. That also happened during World War II, when the South Side Early Learning in Columbus served as a day center so mothers could work while their spouses were at war. At that time, the U.S. government came the closest it ever has to providing universal childcare. When the war ended, so did government support.

Families today are strained in new ways. Page McGinnis, who is director of South Side Early Learning’s four early childhood schools, was shocked by how COVID impacted not just low-income families receiving childcare subsidies, but private-pay families as well.

We quickly saw how even a reduction in hours, not even completely being laid off, just destroyed family budgets and structures,” he said. His staff, including a resident social worker, immediately worked to find resources for strapped families.

“Luckily we’re in the space to know how to work through that because of the population that we serve. But not every early childhood program knows how to serve as that first-stop safety net,” he said.

The struggles of families working second- or third-shift jobs, or those whose schedules change, made front-page news.

“These families have experienced challenges of finding quality care for their kids for years now,” said Kelly Purtell, associate professor of human development and family science and Page McGinnis’ faculty advisor. “All of a sudden, middle-class families started feeling the same issues because they didn’t have childcare easily accessible for them.”

Women, especially, began dropping out across the workforce, sometimes to care for children. Among them were early childhood teachers and workers. Childcare workers and early childhood educators are among the worst paid in Ohio — making a median hourly wage of $10.44 and $12.93, respectively.

Early childhood educators are twice as likely to experience poverty than the average Ohio worker and nearly 10 times more likely than other teachers, according to Policy Matters Ohio.

You can go work at Starbucks and make more money than you would as an early childhood educator,” said Purtell, also a faculty associate at the Crane Center. “That was somewhat true beforehand, but it’s even more true now in this space where so many industries are trying to recruit new employees.”

Still, the ratio of workers/teachers to children is required to be high to ensure a quality environment; the significant cost of providing that care and education is usually passed on to families. The lowest income families can receive free preschool through the federal Head Start program, but eligibility for other federal childcare subsidies are capped at 130% of the poverty line for families in Ohio — among the lowest the nation.

The average cost of infant care in Ohio is $808 per month, or $9,697 annually, for one child.

Care for a 4-year-old costs $658 monthly. A minimum-wage worker in Ohio would need to work full time from January to July just to pay for care for one infant, according to the Economic Policy Institute.

Faced with those costs, especially during a pandemic, some parents simply choose not to work.

The Biden administration’s universal pre-K plan — or even expanded programs that target a wider margin of disadvantaged kids — would boost salaries for pre-K teachers and workers, fund preschool for families of 3- and 4-year-olds and get parents back to work.

“That’s really good for kids,” Purtell said. “Having a stable environment where your parents aren’t as stressed, where they have the opportunity to increase their income — we know all of those things are going to set up a better family dynamic for children.”

Equally important, though, is the “two birds, one stone” effect it could have for closing achievement gaps as children enter elementary school.

Universal pre-K has the potential to be a really great program for children and their families from both ends,” Purtell said, “because it’s helping the families out, but also because it’s providing this incredibly rich developmental environment for kids to thrive.”

But research indicates, and experts agree, universal pre-K alone can’t fix many challenges faced by young children and their families. That, Page McGinnis says, will require even more disruptive innovation — a 21st-century approach to early childhood education.

Old-school models still set standards

As politicians square off on whether to pay for universal pre-K, many make policy decisions based on expectations set for preschools a half-century ago. That’s problematic, said Arya Ansari, assistant professor of human development and family science and faculty associate at the Crane Center.

“Things have changed in the last 50 or 60 years,” he said. Parents have different types of jobs. Care options are more diverse, including public, private and nonprofit centers of varying quality. Some offer early childhood education; others don’t necessarily meet high-quality early learning standards. Children not in preschool live in a wholly different world than their parents and grandparents did.

The landscape is totally different, but we still rely on evidence from back in the day to set the standards for programs in 2021,” Ansari said.

Ansari’s research aims to provide a contemporary lens to view early care and learning. What should we expect from early childhood education in this age of technology, pandemic and growing wealth and opportunity gaps?

Much of his work focuses on ethnically and racially diverse children. His 2019 study showed that diverse and immigrant children who attended pre-K in Virginia performed better academically in kindergarten and had better executive function — the ability to plan, focus, remember instructions and juggle tasks — than children without pre-K.

“We know pretty conclusively that, putting aside the landmark studies from years ago, children enrolled in more contemporary programs enter kindergarten demonstrating stronger math skills, counting skills, improved vocabulary knowledge, listening comprehension, some evidence of improvements in working memory, inhibitory control and cognitive flexibility,” Ansari said.

Nationally, only about half of lower income families choose to enroll their children in preschool or outside care of any kind.

A recent Crane Center study funded by the city of Columbus examined choices parents make for early care and education of children. Ansari was co-investigator.

The findings verify issues what came to light during the pandemic: Families in low-income areas require more flexible childcare options because they work evenings and on weekends. Also, their number one concern is that their children receive quality care.

The study showed that children not receiving out-of-home care spent more time watching TV and playing on tablets or phones. Children in formalized early learning centers spent significantly more time in learning activities and playing with other children. We now know those social and learning opportunities translate to better kindergarten preparedness.

Preschool education holds a great deal of promise,” Ansari said, “but a lot of children are missing out. To maximize the potential and deliver on the promise of preschool, we need to ensure equal access to high quality programs for all.”

A new face of early learning and care?

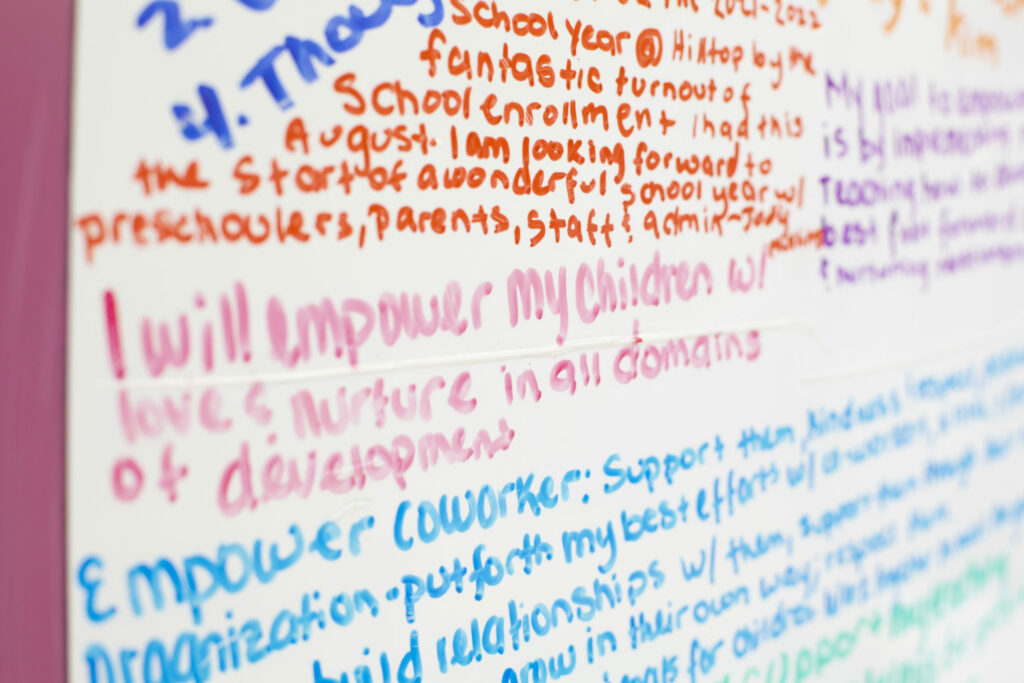

To move the needle for modern working families, early childhood care and education needs courageous innovation, said Page McGinnis. The CEO’s business savvy and academic acumen came together when South Side Learning raised funds to guarantee higher wages for its teachers. The minimum teacher wage of $32,000 annually is now nearly on par with teachers at many public schools.

His research considers why early educators choose to stay in a particular setting — many have been at South Side 20-plus years — while so many have left the field. That turnover hurts young children and undermines parents’ confidence in quality.

“Putting more dollars would help families and help that immediate need,” he said, “but I don’t think it’s going to be maybe as revolutionary for the field of early childhood as we think it’s going to be when we talk about a massive program like universal.”

A new model for early childhood education should meet families where they are, he said, starting with evening and weekend care to accommodate shifts of hospital and factory workers.

We’ve actually been kicking around the idea of what would 24-hour care look like,” he said. “What would it look like to be open full day, all day, with different (teacher) shifts?”

Imagine teachers leading learning as children eat breakfast and brush teeth. “How do you incorporate more of those academic outcomes in the morning right before pickup?”

Universal pre-K would get more 3- and 4-year-olds into early childhood education, but infants and their families can’t wait.

“The window really is nine months to about 30 months for all the rapid brain development, for all the rapid pro-social things,” Page McGinnis said. “We should be thinking about not only investments in pre-K, but how do we invest in robust, infant/toddler, high-quality programming, where we put more supports at the beginning?”

Those providers help foster critical language development, engage in gross motor skills, create activities that will lead even babies to reach developmental milestones.

Some providers and experts worry that government-led universal pre-K could legislate out all the innovation and options families now use. Among those are regulated home care by providers trained to creatively engage in early learning.

“We don’t want to standardize too much,” Purtell said. “Different parents have different needs and can be better served by different options. What we need is a system that provides parents with alternatives, but also with an underlying thread of quality and providing good experiences to children while they’re there.”