How scholarship and a community turned a mentee into a mentor

Mentoring is messy business. No one knows that better than James L. Moore III. For years, the EHE Distinguished Professor of Urban Education has made leaders of young black men. He finds them, coaches them, awards them scholarships. Some take unorthodox paths. But when Moore saw one of his Weiler Scholars asleep on an airport floor early one semester, it gave him pause.

Tim Jones, ’18 BS, was awaiting a west-coast flight. Moore chose not to say anything to him. “The man who saved my life had no idea I was running away,” Jones later said.

Jones was an inner-city kid with real promise — though he didn’t always believe it. He is also a miracle magnet. Five-feet, five-inches of guts and attitude, Jones regularly landed in the principal’s office as a kid.

Eugene Caslin, ’93 MA, was his coach and first black male teacher. Jones finally made the basketball team his senior year — after trying four times. In class, Caslin said, “I saw the potential from the beginning. I could tell he wanted to learn.”

Jones applied late to Ohio State and was accepted, but couldn’t pay. Speaking at a youth revival that August, he spilled his predicament before the church congregation. “I broke down,” Jones recalled. His choir had just sung about receiving “exceedingly, abundantly, all you can ask for.”

Within days, the church raised $8,000 for his tuition — the miracle he needed. But being new at this, Jones mistakenly thought he owed fees for the entire year. His dad encouraged him to go to Ohio State’s early arrival program anyway. He did. One connection led to another, and Jones found himself summoned to Moore’s office.

“He came in and said, ‘Dr. Moore, did I do something wrong?’” Moore recalled.

Did he want to be a teacher in an urban setting, Moore asked. “Yes, sir.”

“Will you give up on those kids?”

“No, sir.”

“How about when your back is against the wall?” Moore pressed him. “It’s dismal and the kids have all this stuff going on. Are you going to work with them, or are you going to throw them away?”

“I’m going to help them, the way I’ve been helped,” Jones said.

Jones was just the student Robert and Missy Weiler had in mind when they funded a scholars’ program for male, African American urban education majors. That day in Moore’s office flipped Jones’ world; the scholarship paid his tuition, living expenses, books. The loans he had hastily obtained were erased.

“This figure comes into my life, telling me all I had to do was a good job at what I already wanted to do anyway,” Jones said. “Everything was taken care of instantly.”

Except that money alone is never an instant fix.

“It requires high-level success coaching,” said Moore, also a professor of counselor education. “Don’t think because you give a kid money that’s going to change their reality. They thrive when they have structure and coaching and goal setting. After a while they start thinking they did it on their own.”

Jones earned a 4.0 GPA his first semester. But his old life was immersed in African American culture. Now he might go all day without seeing another black student in class. He had the highest ACT score in his high school. At Ohio State, he felt merely average.

“Tim was a lone ranger,” Moore said. “I can talk about it because I was a lone ranger. It’s lonely. It’s lonely for me even now.”

“It was culture shock,” Jones said. “In that longing for yourself, you’re like, it’s not for me. It must not be for me.”

When a romantic relationship ended badly, he broke. And he ran. For three months in San Diego, he bused tables and lived in a tiny, flea-bag rental. He got into sticky situations he’s not proud of, and sank deep into depression. He saw things he can never erase. And he was alone. Really alone.

But he kept hearing Moore’s words. “Will you give up on those kids?” He couldn’t. And he desperately wanted to make his mentor proud. He began to find his purpose.

“I was kept and made to be safe, to experience all this. It was for a reason. God brought me back. I’ve always believed that wisdom is not stagnant but transcends time. As humans, we’re to pick up knowledge and pass it down.”

He wanted to be that vessel. With two weeks left in the semester, he rushed home and pulled off a 2.3 GPA. Later he’d make the dean’s list. But the lessons he’d learned — even through the rough spots — were invaluable.

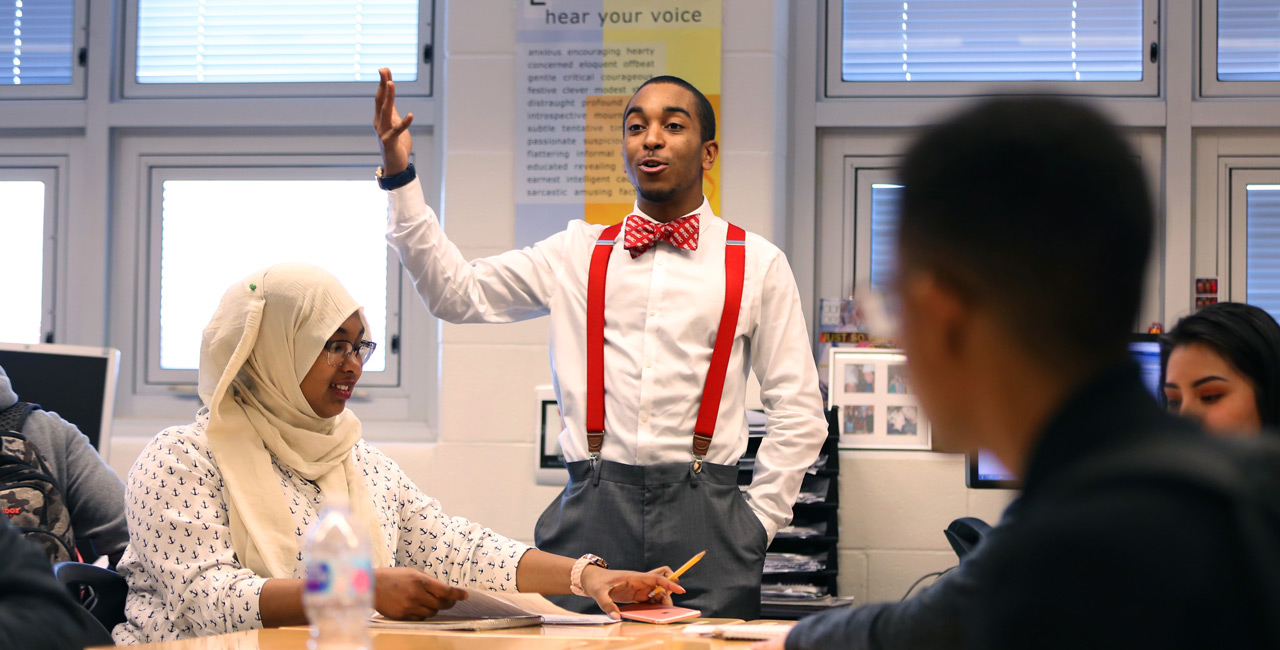

While student teaching last fall, he asked a student why she hadn’t done an assignment. She shared a toxic family situation. Because of his time in San Diego, he got it.

He yearns to guide kids like her to a better place.

“I want to be there when they figure it out. They’ll say, ‘Oh, I want to be that.’ I’ll be like, ‘Yeah, now go do it!’ I want to be that person, because that’s what Dr. Moore was for me.”