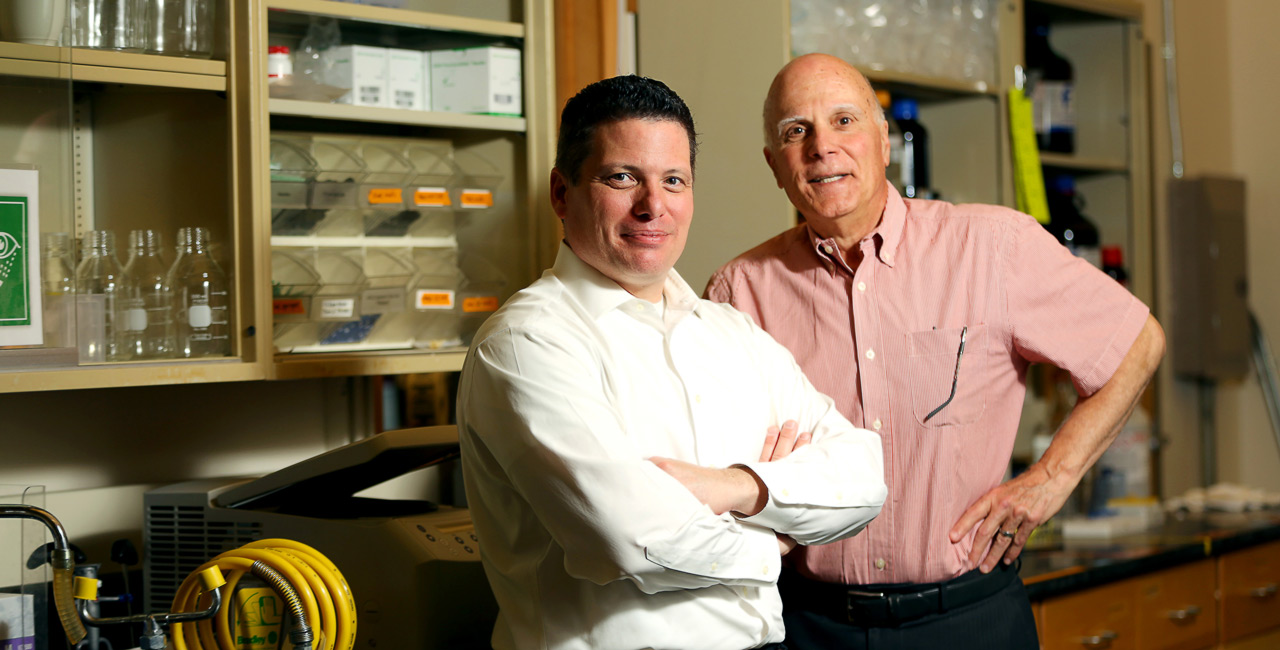

They once were professor and advisee. Now they’re colleagues. And that’s the end goal, they say.

BY ROBIN CHENOWETH

Accomplished nutrition scientist Kelly Walsh, ’00 BS, ’06 PhD, was an untried grad student when he first crossed paths with the man who would set his career into motion. He was intimidated, to say the least.

“Here’s the chair of the department,” he recalled. “He’s a gruff guy who’s an amazing scientist,” one of the most highly regarded nutrition researchers in the country. Fumbling with keys outside the graduate student office, Walsh blurted, “Hi, Dr. Failla.”

“Whoa, whoa, whoa!” Mark Failla retorted. “What did you call me?” Walsh winced, assuming he’d mispronounced the name.

“How much do you pay for a cup of coffee?” the professor barked.

“I don’t know, $1.50?” Walsh offered. “Me, too. When I get it cheaper you can call me Dr. Failla. Until then, it’s Mark.”

Failla, most recently interim faculty lead for Ohio State’s Foods for Health Discovery Theme, doesn’t recall the encounter. He remembers a fresh-faced, ex-Army specialist showing up, asking to do research in his lab.

“He performed so well in a relatively short time and expressed interest in getting a PhD” in the OSU Interdisciplinary Nutrition PhD program, said Failla, now faculty emeritus. Walsh’s degree in engineering intrigued him.

“I knew he had to be quantitative. We said, this guy’s PhD material. Pass go, collect $200, forget the master’s.”

Terms set, the two forged a relationship tested by countless hours in the lab and more than a few over the Failla family dinner table.

Their research centered on isoflavones — soy-derived compounds with weak estrogenic activity that might block the action of natural estrogens in the body. These could lower rates of heart disease and breast cancer in women — but only if the compounds were properly absorbed in the intestinal tract.

Early on, Walsh chewed untold mouthfuls of soy bread, which he spat into vials to measure how saliva affected the stability of isoflavones during initial digestion.

“The general question for inquiry came down to, where in the gut are these compounds being absorbed?” Failla said. “We were interested in what’s going on in the small intestine versus the large intestine.”

Pigs are good human surrogates for digestion, so Walsh fed them cherry Kool-Aid mixed with a colon cleanse product — a necessary step before conducting their intended study. “We’d be able to collect what comes out and see how much of our compounds of interest are there,” Failla said.

There were times he showed genuine compassion. And there were times when it was, ‘Suck it up, buttercup; get back in the lab.’

– Kelly Walsh

Problem was, zero-hour fell on Walsh’s birthday. Failla sent his protégé to dinner with his family and set up shop at the business end of the pigs.

“The smell of a pig barn permeates your skin and stays with you,” Walsh recalled. “I come back and he’s sitting on a bucket — in the blast zone — grading papers. He hands them back in class and people are saying, ‘What is the smell?’” Mentoring, it seems, is not without sacrifice.

But the pig study was translated into a human study, and Walsh became lead author for articles in Molecular Nutrition and Food Research and the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. National presentations followed.

Failla’s mentoring style is blunt, irascible and at times tender. He loves mingling with students in the lab and tinkering with their projects.

“There were times he showed genuine compassion. And there were times when it was, ‘Suck it up, buttercup; get back in the lab. I don’t want to see you until you’ve got data in your hands,’” Walsh said.

Walsh recalls the grilling by Failla and faculty leading up to national presentations. “He says, ‘We’re going to beat you up in here. We’re going to leave no stone unturned … critiquing the science so when you present publicly you’re completely buttoned up.’”

Walsh now appreciates the toughness. “When you get into the real world and interact with people who didn’t have such thorough training, you think, ‘How did you not know that?’ It’s not intelligence. It’s training.”

The real world, for Walsh, is Mead Johnson Nutrition in Indiana, where he is the research and development director for global clinical research. He invented a patented human milk fortifier that has helped over 30,000 premature infants grow and develop. He manages a research team and mentors postdoctoral researchers, including Failla’s Fabiola Guitierrez-Orozco, ’09 MS, ’14 PhD, also at Mead Johnson Nutrition.

Both men say the mentoring circle never ends. Walsh recently read a book chapter, “an epiphany” about mentoring. Its exhaustive list of characteristics — being accessible, a good listener, willing to share knowledge — all applied to his advisor. “He continues to mentor throughout life,” Walsh said.

But at some point, the paradigm shifts. Failla’s own PhD mentor explained when it’s time to let a student move on. “It’s when you’re really confident they’re going to make more contributions than you’ll ever make,” he said.

“These aren’t my students anymore. They’re colleagues and friends. The great joy for me is they survived me. I take real joy in seeing their continued maturation and success.”